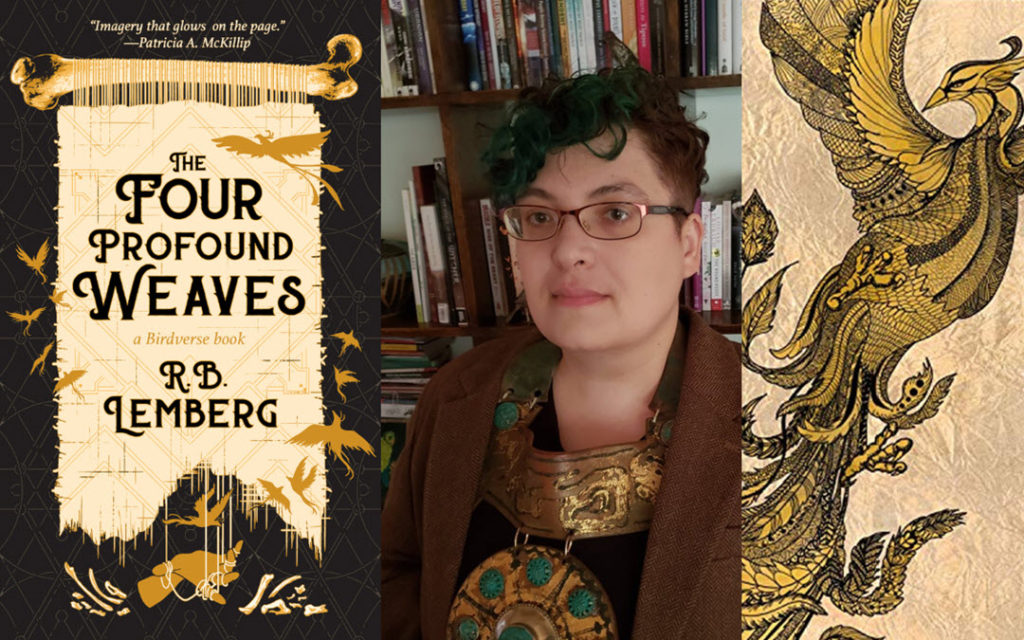

R.B. Lemberg

“I am in the end . . . a creature of the work, of deep storytelling, and of imagination. In Lemberg’s novella, I find all three. “

When I read R.B. Lemberg’s novella, The Four Profound Weaves (2020.) [1] I expected not to like it but I hoped, very much hoped, that I would.

Reader: I did, very much did.

I expect to not like most things I read. I am something of an impatient reader. It is my private idiosyncrasy. It tends to flare more often when I read fiction. Non-fiction, it seems, just annoys me as it is often a matter of sloppy thinking, bad-writing, incorrect information, etc. (though I draw the line at plagiarism). These are not good things, but I tend to cut a non-fiction writer a little slack. The younger ones anyway. Experienced oldsters should know better and deserve every ounce of flack thrown their way.

Poets get all the slack and all the love from me. Poetry is its own universe. I go there, I write there, and I know that the poet’s mind is the mind of an artist who, as Ursula K. Le Guin noted, goes

“into the gap between . . . . They go limping and weeping, ugly and frightened, and they come back with the wings of the redwing hawk, the eyes of the mountain lion.” [2]

Fiction writers, many of them anyway, are artists too. And I try to temper my readerly temper on their behalf. Writing isn’t an easy craft. I know this. So to come upon a story that takes me into it then lets me walk back into myself and back again, well, it’s a rare work that can create that two-way bridge and make it an easy yet challenging walk.

The Quality of Craft

R.B. Lemberg’s The Four Profound Weaves is such a story. I am a long time reader of Ms. Le Guin. Her work is crafted down to the molecules as writing and to the subatomic in terms of story. One feels utterly held by her. Lemberg’s novella holds a comparable easeful regard of its readers while pushing, pushing that deeply reflective quality one hopes to find in works of imagination. There is world building and there is cosmology. Lemberg has managed to do both and, fittingly, woven them together so that each one is visible, yet not, while informing the other.

I will not summarize the story. Other reviewers have done this better than I could (See Foreword Reviews or Publishers Weekly). My intent is to relay my immediate response as a reader. (I wrote my notes for this post an hour after reading the book.)

For me the heart of a fiction work is character. I want to know the persons almost more than I want to know the plot in which they are encased. So I am sensitive to point of view. As a reader I typically balk at first person narration. It is too easy, I think, for the author to channel themselves. Solid, credible first person point of view is hard to master.

Lemberg does master it, twice, their chapters alternating between two trans “elders,” former/current friends, who travel together on a quest to find the aged aunt of one, a legendary weaver. One, Uiziya, seeks to know how to weave a carpet of bones, the other, nen-sasaïr, the so-called nameless man, to learn their new name. By narrative necessity their tales overlap, but who they each are, who they perceive themselves to be, what their respective “mission” is, what they each hope for, is succinctly delineated. They are different people but their cultures overlap, they have awareness of the other cultures. So it could have happened that Lemberg’s “first persons” could have sounded like one person. They do not. And the characters themselves are vividly rendered in voice, movement, beliefs, history, and emotion/psychology. They are real, which is something quite powerful when the story is not simply fiction, but fantasy fiction.

Opening Lines

Another thing that either catches me or doesn’t are the opening lines of the first chapter. Personally, I hate it when literary agents (on Twitter is where I tend to see this) harp on the importance of opening lines. But they are right for the most part. It’s not simply the content of those sentences, though one hopes they set the tone for the story and, if one is lucky, the whole damn story itself.

The opening two sentences of Four Weaves are “I sat alone in my old goatskin tent. Waiting, like I had for the last forty years, for Aunt Benesret to come back.” I laughed, out loud. For in that split second I recalled the opening lines of three other authors I’d read recently and semi-recently, all trying something similar with varying degrees of—to my eye—success. (Disclaimer: I do not presume that my take is anyone else’s but my own.)

“The steerswoman centered her chart on the table and anchored the corners around. A candlestick, a worn leatherbound book, an empty mug, and her own left hand held the curling parchment flat.”

“Matt said you find things. For a living,” the woman said on the phone.”

“There was a wall. It did not look important.”

The first is from Rosemary Kirstein’s The Steerswoman, described as a science fantasy novel. It is the first of a series. Established here: who, something of a setting, an overall tone, and that wonderfully curious phrase, “her own left hand.” [3] The opening description was slightly cliché but that single phrase–her own left hand–caught me. It was a quality of character subtlety that intrigued. Going forward, I read the first three books, I was very much intrigued by the tale but the writing kept tripping me. Description overrode things, the “own left hand” turned out to be a phrase quirk and no more. The story got lost in the telling. I didn’t read book four and book five has yet to be completed.

The second is from Kristen Lepionka’s 2017 mystery novel The Last Place You Look. Typical noir in cadence, snarkish tone, and an anonymous caller. [4] I know I probably shouldn’t, but I laugh at that noir verbal tic. I can’t take it seriously. I didn’t get beyond the first chapter. I couldn’t, and I wanted to. But time is precious and I only read what I want to read.

The last is from Le Guin’s SF novel The Dispossessed. The cadence is the same as Lemberg’s opening two sentences. Setting, tone, context nailed in nine words. [5] I have read most of what Le Guin has written, fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. I don’t like everything she’s done but I’ve read it. Not simply because she is a master at the craft of writing and an imagineer, world builder, and cosmologist of the highest level. She exudes the power of a soul sorted, explored, and faced with ruthless honesty. I am drawn to her in a way I am drawn to no other author.

A Singular Author

Lemberg does that for me and, frankly, I am floored. I came across them only recently and incidentally, someone I follow on Twitter mentioned them. Perhaps they quoted them, I don’t recall but I was curious. I started to follow them and saw mention made and discussions shared about this new work coming out that had a flavor of originality. I am keen for new stories. There was something else, though, a personal grief, which the nature of Twitter meant it was a public grief. I have been touched by the quality of their expressions and efforts in this deeply mournful time. There was grief, but an ineffable connection with life too.

I typically avoid seeking out the personal about an author. I want their stories, I don’t want them. I believe writers, like everyone, are owed their privacy. That I know what I do about Le Guin is mostly due to the scholarly articles I’ve read about her, the personal remarks she makes in her essays and writing instructionals, and Arwen Curry’s splendid documentary, Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin. I honored Lemberg’s mourning but did not, as a stranger, want to in any way intrude.

I preordered The Four Profound Weaves and, in awaiting its arrival, did something I never do. I avoided all reviews and all commentary as best I could. I don’t mind spoilers, so it wasn’t that. It seemed to me that this book might be the kind of book that gave my angry reader self a needed calming down. I have never before so prepared myself to read like this. And I am grateful that I was not disappointed.

I am in the end, I guess one might say, a creature of the work, of deep storytelling, and of imagination. In Lemberg’s novella, I find all three. They craft their writing. There is cadence to the sentences, the narrative flow, and the plot itself. They know how language works to deepen the culture surrounding people and their doings. Character names sound real. The words used to describe artifacts, cultural behavior, the sociology of the different peoples all ring true. With regard to the journey that is imagination, Lemberg bends their mind (and heart too, one senses) into that gap between and emerges with the wings of the redwing hawk. This tale seems to have been torn from their soul.

The Four Profound Weaves is an unexpected gift. In Lemberg’s Birdverse context, I am an elder (though I do not feel like one). I have not felt as young as I do now, as a child looking forward to sitting at their feet, awaiting future tales. I am grateful to know that their stories are and will continue to be told after I am no more.

NOTE: This essay is a lightly edited version of one I originally published on 2 Sept 2020 on my blog Dante’s Wardrobe.

© J.A. Jablonski 2021. All rights reserved.

ABOUT BOOK THOUGHTS

“Book Thoughts” is an intermittent column within my blog. The essays are not so much book reviews as a book responses. I like to converse with and around the books I read.

HOW TO CITE THIS POST

Jablonski, J.A. (2021, Aug 30). R.B. Lemberg | The Four Profound Weaves. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website). https://jajablonski.com/2021/08/30/four-profound-weaves/

IMAGE CREDITS

Cover of The Four Profound Weaves. From Lemberg’s website.

R. B. Lemberg. Author photo from Lemberg’s Press Kit.

Modified cover image of bird from Audible version of book.

Silhouette of exotic flying bird. From the Tachyon Press page for The Four Profound Weaves.

SOURCES

Disclaimer: As a Bookshop Affiliate (US only) I will earn a commission if you click through on a book title I’ve linked to and make a purchase.

[1] Lemberg, R.B. (2020). The Four Profound Weaves. Tachyon.

[2] Le Guin, Ursula K. (1985) Always Coming Home. Harper & Row, pgs: 74-75.

(Bookshop link is to the University of California edition.)

[3] Kirstein, Rosemary. (2019). The Steerswoman. Published by Rosemary Kirstein.

[4] Lepionka, Kristen. (2017). The Last Place You Look. Minotaur.

[5] Le Guin, Ursula K. (1974). The Dispossessed. Avon Books.

(Bookshop link is to the Harper Voyager 1994 edition.)