“Her removal of RLS from the biographical context allows her to position him

in relation to his social and literary peers as simply that,

peers, which in turn lets her discuss those peers on their own merits.”

It’s been a while since I’ve motored my way through a scholarly text for the fun of it. As an academic (educator and librarian) in the humanities and social sciences I’ve taught literary criticism, research methods, and professional and academic writing. And I’ve indexed a goodly number of scholarly books and unnumbered scholarly articles. So this is something of a busman’s holiday.

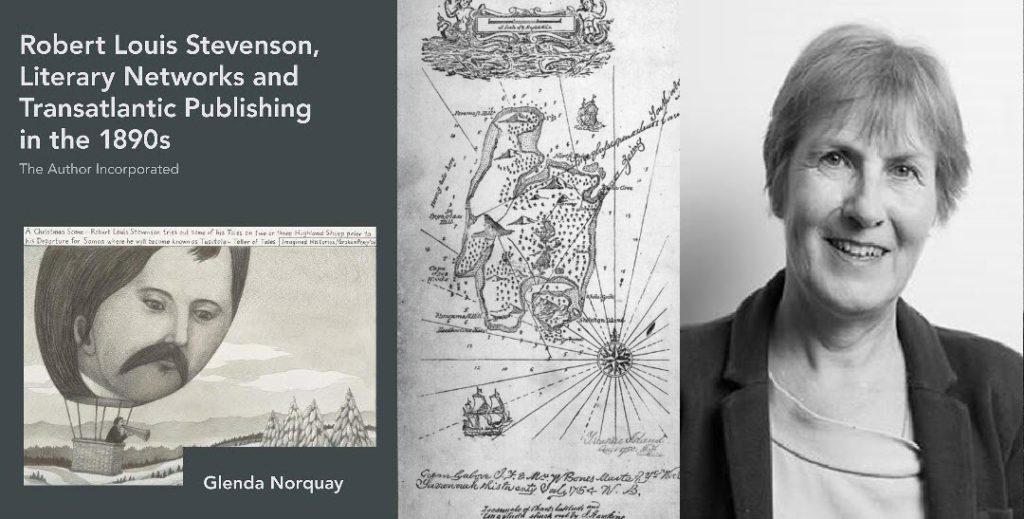

A disclaimer, however: My thoughts in this essay are not so much a book review as a book response. I like to converse with and around the books I read. The book in question is Glenda Norquay’s Robert Louis Stevenson, Literary Networks and Transatlantic Publishing in the 1890s: The Author Incorporated (Anthem Press, 2020). [1] And a second disclaimer is necessary. I am by no means a Stevenson scholar; I am a dilettante at best. I came across the gent perhaps two years ago while looking for a quotation to use as a chapter epigraph for a mystery novel I am writing. That led me to his letters, then his essays, then to a run of biographies about the man. I’ve yet to read much of his fiction.

Here is a section of the summary of Norquay’s book provided by her publisher, Anthem Press:

Reading Literary Networks (as I shall refer to Norquay’s book) was a bit like reading two books at once. Scholarly writing can be pedantic and weighty but I didn’t see that here. Norquay’s Introduction is necessarily dense but she outlines her theoretical approach straightforwardly in graceful prose. It is here she lays the groundwork of the book re: geography and the history of publishing in Stevenson’s time.

Reading Literary Networks (as I shall refer to Norquay’s book) was a bit like reading two books at once. Scholarly writing can be pedantic and weighty but I didn’t see that here. Norquay’s Introduction is necessarily dense but she outlines her theoretical approach straightforwardly in graceful prose. It is here she lays the groundwork of the book re: geography and the history of publishing in Stevenson’s time.

That is how I started reading it, as groundwork, but as I neared the end of the section, the notion of literary networks became personalized. As she proceeds into the book proper, taking as the focus in each succeeding chapter a single influential person in Stevenson’s life, or group of persons in the case of his family, Norquay’s take on things assumes an increasing momentum and power. This is a work of concision and insight.

Stevenson is presented as a person outstanding, not a creature enmeshed in his biography as is often the case. He is himself, a man in transition at a time of transition. Norquay’s removal of Stevenson from the biographical context—she is keenly aware of this well-trod territory and how it has the tendency to make biographies of Stevenson narratively redundant—allows her to position him in relation to his social and literary peers as simply that, peers, which in turn lets her discuss those peers on their own merits. She gives Stevenson a larger space within his own time. Literally larger, in the geographic sense and chronologically in relation to his literary contemporaries. Norquay’s conceptions lets us view Stevenson as responding, if only instinctively, to the transitional nature of that era’s publishing approach, to the changing notions about intellectual ownership, and to the traditional, idealized creative process of the author.

For all that Literary Networks is not a deliberate biography, the chapter case studies on Lemuel Bangs, Charles Baxter, Sidney Colvin, Stevenson’s immediate family and friend-collaborators, Arthur Quiller-Couch, and finally, Ricard Le Gallienne act to mirror Stevenson, reflecting who and how Stevenson was in a way more singular than mere biography might achieve.

THE NOTION OF TRANSITION

Literary Networks provides me with a welcome and unexpected context. My personal interest is in the creative process as a topic and in and of itself. I always land on the transitional moments: the twelfth-century Renaissance, the period of incunabula leading in to the age of the printing press, the so-called Industrial Revolution (especially in the United States), and the rise of the internet in its publicly accessible mode. Such liminal moments fascinate me and charge my creative approach. [3]

Transition, in its dual meaning as change and progression, operates on a personal level for Stevenson. His friendships and relationships, the really critical ones, have a creative and imaginative intimacy to them. He is a willing collaborator (if a sloppy businessman). As time progresses, as his social environment changes, he matures as a writer in terms of craft but, more intriguing to me, in terms of his imagination. That, I confess, more than the specifics of the matters of international publication and copyright are what stayed with me after reading.*

* Though I must hasten to clarify: As a student of writing history I find Norquay’s analysis of the transitions in the publishing industry, the subsequent contrasting approaches to the development of a reading community, and the notion of the popular versus literary value of Stevenson’s work to be virtually a separate, and most valuable, addition to my scholarly library.

Transitioning to Self

Until Stevenson took up permanent residence in Samoa, his nomadic ways—fueled by medical necessity in most instances though by personal and emotional necessity as well—were regarded by his personal and literary friends as a quirk. His travels fueled his writerly imagination and a reading public’s romantic notion of him. His time in Samoa changed him, however, much to the consternation of those who sought to publish on his behalf and, as Norquay considers, who might use their connection with Stevenson to personally or professionally profit on their own behalf.

Always complex psychologically, Stevenson’s engagement with Samoan politics, his responsibilities as literal and local clan patriarch, and an increasing sensibility that he was finally his own man, led him to write what he pleased or perhaps more accurately, write about matters closest to his heart: a broken relationship with a father and rich relationships with strong women.

Writing to his beloved cousin Bob Stevenson three months before his own death Stevenson muses on the notion of family, his own, over previous centuries. He says

What a singular thing is this undistinguished perpetuation of a family throughout the centuries, and the sudden bursting forth of character and capacity that began with our grandfather! But as I go on in life, day by day. . . I cannot get used to this world, to procreation, to heredity, to sight, to hearing, the commonest things are a burthen. . . . The prim obliterated polite face of life, and the broad, bawdy, and orgiastic–or maenadic–foundations, form a spectacle to which no habit can reconcile me.” [4]

Here is a man who lived his entire life expecting death at any moment, who conformed then fought conformity, who turned away from the “polite face of life” to find his own face. Such an intensely personal and intimate life journey playing out over two oceans and multiple letters. And, it seems to me, within Literary Networks. It is a powerful work of scholarship to be sure. It seems, though, anyone taking on Stevenson takes him on his own terms. In discussing the development of her book, Norquay says she initially thought it would be

“. . . primarily text-based. Talking about ‘St. Ives’ . . . about ‘Weir of Hermiston’ . . . . but in a way it’s become more about the characters around Stevenson and their very different perceptions of Stevenson as an author and their very different engagements with him . . . .” [5]

Novelist and critic (and one of Norquay’s case study subjects), Arthur Quiller-Couch, describing him as their lodestar, reflects a perpetual present tense quality of Stevenson, a kind of enmeshment, where he is continues to be viewed through a personalized, present-tense lens by family, friends, and colleagues.

Norquay, by using the different frame of geography and literary mobility, frees Stevenson from the focused, limiting role of lodestar. His influence, she shows us, is more far-reaching in the spaces of authoring and publishing and long after his fiction had gone out of literary fashion.

REFLECTIONS

My tendency as a reader is invariably trinary, with my focus on the pragmatic, the associative, and that which I call the originative flux. As a pragmatic reader I take the story or text as is looking at or for the narrative who, what, when, why, and how. Problematic, sloppy, or casual writing annoys and distracts. If fiction, I wish to be taken, persuaded, challenged, entertained; if nonfiction I want to be informed, accurately and insightfully. And I want the writing done with grace, style, and some measure of verbal power.

My tendency as a reader is invariably trinary, with my focus on the pragmatic, the associative, and that which I call the originative flux. As a pragmatic reader I take the story or text as is looking at or for the narrative who, what, when, why, and how. Problematic, sloppy, or casual writing annoys and distracts. If fiction, I wish to be taken, persuaded, challenged, entertained; if nonfiction I want to be informed, accurately and insightfully. And I want the writing done with grace, style, and some measure of verbal power.

As an associative reader I invariably, and involuntarily, associate what I am reading with whatever the reading might trigger, be that something else by the same author, or a different author, or a movie, or an image, or a comment from social media, a costume, a dream . . . whatever the text calls to mind. It is a combination of Rabbit Hole Syndrome and a kind of spontaneous and unpremeditated mind mapping. It can be massively distracting and intensely pleasurable.

The reading experience of originative flux, a mode that, like the muse does not always materialize, is something of a constant. My curiosity about the origination and the flux of creation is deep and voracious. I cannot but crave knowing the mind behind the making. Not the person, necessarily, though that may happen along the way. (I try to avoid parasocial interactions with creative others, not always successfully.)

Norquay captures me on all three levels. One of the delights in reading Norquay’s book is seeing a mind work in such a large way. Literary Networks is a work that manifests considerable scholarly range yet Norquay wears that mantle lightly. It enhances my personal experience as a reader. That her writing style is easy—in that it flows, is crafted yet not overwrought, is intellectually accessible while challenging—heightens my enjoyment. I delight in seeing an idea well-formulated and explained in the same way I find joy in seeing a perfectly executed double play in baseball or hearing the perfect balance of polyphonic music. I very much look forward to reading her other work.

Author Info. Glenda Norquay is Professor Emerita in Scottish Literary Studies at the Research Institute for Literature and Cultural History at Liverpool John Moores University. Her research focus is twofold: Scottish writing, specifically women’s fiction, the nineteenth-century and contemporary novel; and Robert Louis Stevenson’s fiction, criticism and publishing history.

Author Info. Glenda Norquay is Professor Emerita in Scottish Literary Studies at the Research Institute for Literature and Cultural History at Liverpool John Moores University. Her research focus is twofold: Scottish writing, specifically women’s fiction, the nineteenth-century and contemporary novel; and Robert Louis Stevenson’s fiction, criticism and publishing history.

In addition to the book I am considering here, Norquay has two other books on Stevenson: a monograph, RLS: Robert Louis Stevenson and Theories of Reading: The Reader as Vagabond, and R.L. Stevenson on Fiction: An Anthology of Literary and Critical Essays. She is currently editing his unfinished novel, St. Ives: Being The Adventures of a French Prisoner in England for the New Edinburgh Edition of Stevenson.

If you have a question or comment for me, drop me a line via my Contact page.

© J.A. Jablonski 2022. All rights reserved.

ABOUT BOOK THOUGHTS

“Book Thoughts” is an intermittent column within my blog. The essays are not so much book reviews as book responses. I like to converse with and around the books I read.

HOW TO CITE THIS POST

Jablonski, J.A. (2021, Dec 6). Glenda Norquay’ | Robert Louis Stevenson, Literary Networks and Translatlantic Publishing in the 1890s. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website). https://jajablonski.com/2021/12/06/glenda-norquay/

IMAGE CREDITS

Header image

-

- Cover of Glenda Norquay’s book, Robert Louis Stevenson, Literary Networks and Translatlantic Publishing in the 1890s: An Author Incorporated. From publisher website (Anthem Press).

- “Stevenson’s map of Treasure Island.” From Wikipedia, listed as in the Public Domain.

- Glenda Norquay, author portrait. From Professor Norquay’s Liverpool John Moores University profile.

Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson by Henry Walter Barnett, 1893. Modified using the Picas art photo filter. Original image is in the public domain.

Portrait of J.A. Jablonski by Mike De Sisti. Used by permission.

Portrait of Glenda Norquay. From Professor Norquay’s profile for The Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, The University of Edinburgh.

SOURCES

Disclaimer: As a Bookshop Affiliate (US only) I will earn a commission if you click through on a book title I’ve linked to and make a purchase.

[1] Norquay, Glenda. (2020). Robert Louis Stevenson, Literary Networks and Translatlantic Publishing in the 1890s: The Author Incorporated. Anthem Press.

[2] About this Book. (n.d.) Anthem Press.

[3] Works on historical transitions that I especially like:

-

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth. (1980). The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge.

- Haskins, Charles Homer & Haskins, Jim. (2005). The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. Harvard.

- Schlereth, Thomas J. (1991). Victorian America: Transformations in Everyday Life, 1876-1915. HarperPerennial.

[4] Letter to Bob Stevenson, 9 September 1894. The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, vol 8, January 1893-December 1894. Letter #2782. Yale University Press, 1995, pg. 362).

[5] Norquay, Glenda. (2020, Nov 16). Robert Louis Stevenson Inc. | Prof. Glenda Norquay | LJMU English. YouTube video. Runtime: 15:14. Description: “Norquay discusses her new book about the transatlantic publishing networks of Robert Louis Stevenson and his literary circle.” The quotation above begins at timestamp 2:45.