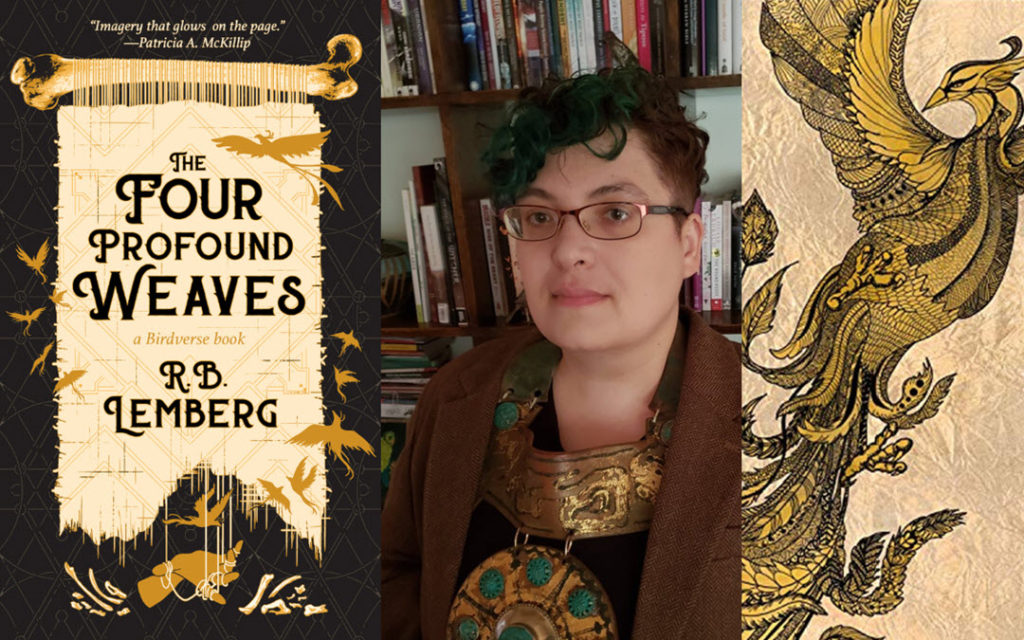

Liza Kirwin | More Than Words

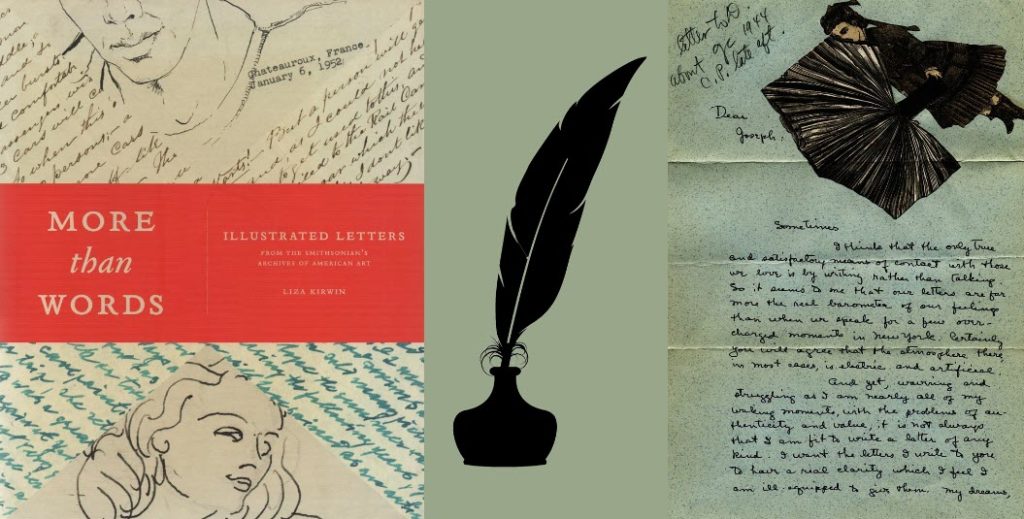

Left: More Than Words book cover | Right: Letter of Dorothea Tanning to Joseph Cornell (1948)

“. . . they capture not simply eras but moments and personalities. They are legacies each one, though minute.“

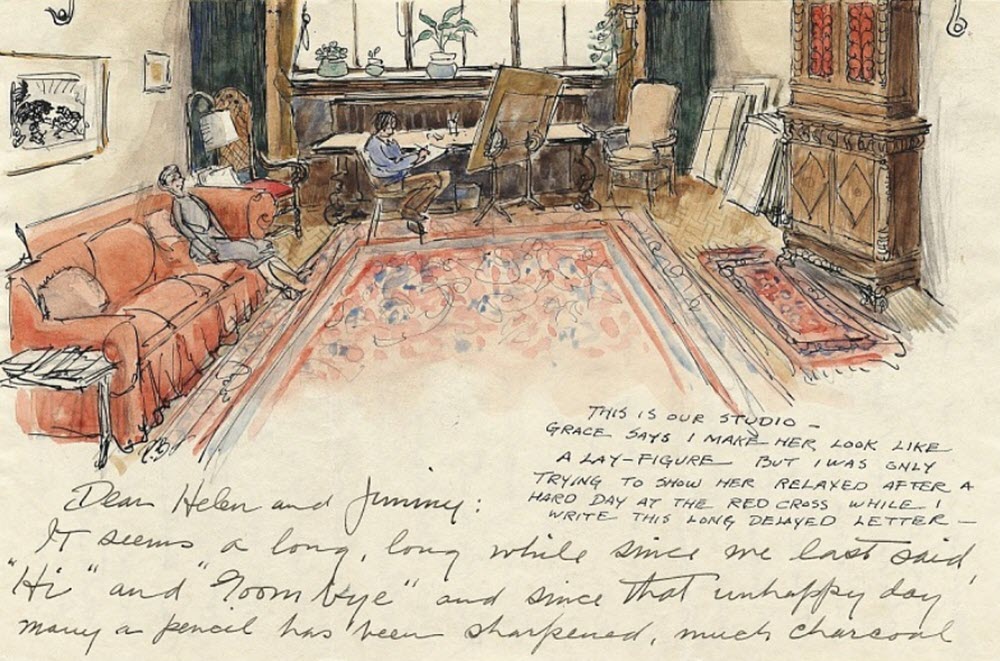

Letter by Paul Bransom to Helen Ireland Hays

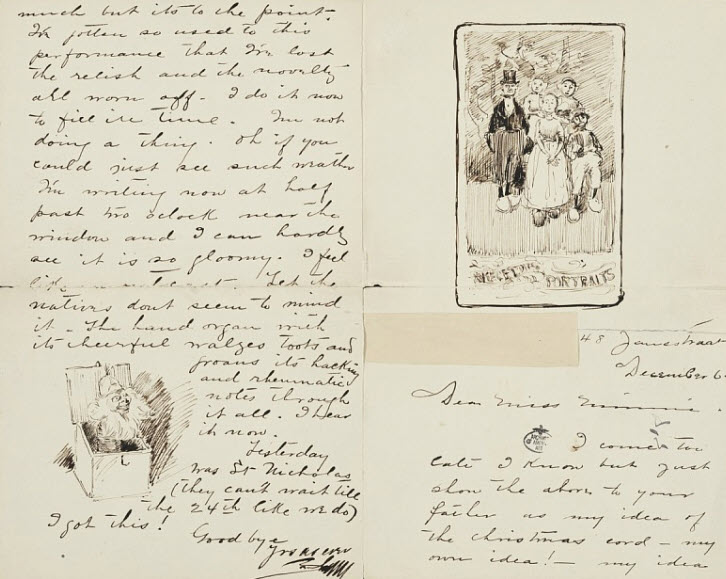

Robert Frederick Blum to Minnie Gerson, 1883 December 6.

The transcriptions in the appendix are jewels. Not all antique (one letter was posted in 1963); they capture not simply eras but moments and personalities. They are legacies each one, though minute. So strongly present is the sense of making: of friendships, of connections, of the letters themselves.

Letter Writing as a Movement

The final paragraph of the Introduction urgently notes the loss of these material treasures that are “all but disappearing from our culture.” I am less convinced that this is so. The Mail Art movement has been running strong for half a century now. I regularly come across websites dedicated to either mail art or letter writing specifically (see below). And the Maker Movement, the Steampunk movement, and rise of elaborate cosplay events all bespeak a yearning for solid, physical and playful culture that is being energetically acted upon. Twenty-first century letter writers are not so much looking looking back as creating their own legacies of now.

The final paragraph of the Introduction urgently notes the loss of these material treasures that are “all but disappearing from our culture.” I am less convinced that this is so. The Mail Art movement has been running strong for half a century now. I regularly come across websites dedicated to either mail art or letter writing specifically (see below). And the Maker Movement, the Steampunk movement, and rise of elaborate cosplay events all bespeak a yearning for solid, physical and playful culture that is being energetically acted upon. Twenty-first century letter writers are not so much looking looking back as creating their own legacies of now.

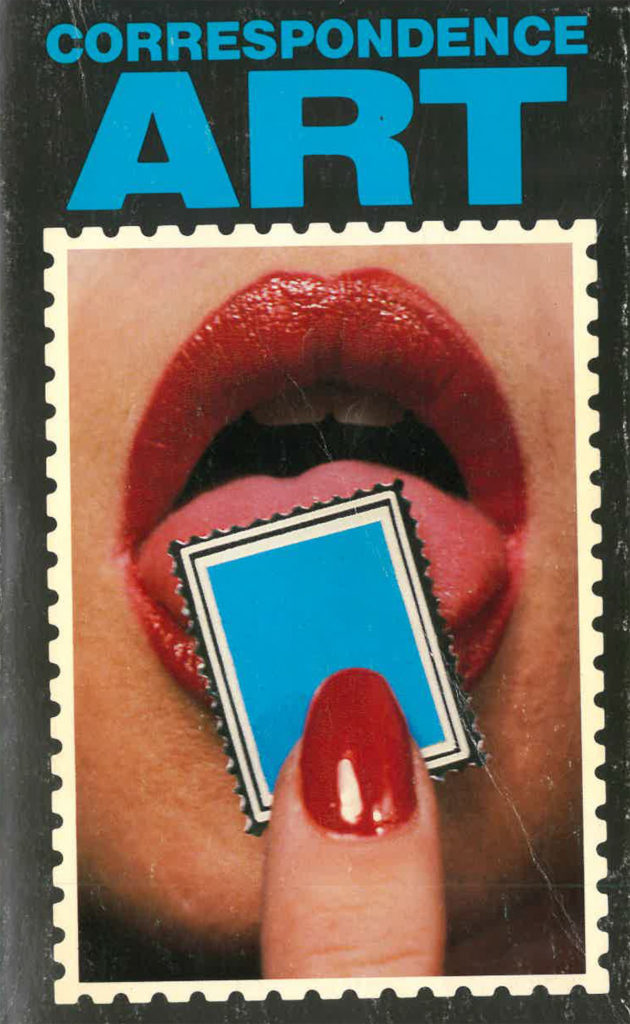

In the 1960s performance and conceptual artist, Ray Johnson, spearheaded the mail art (or correspondence art) movement. According to the Artists’ Pub network site “Mail Art does not refer to the personal correspondence between two individuals but the communication with art about specifically announced projects.” [2]

The long out-of-print book Correspondence Art: Sourcebook for the Network of International Postal Art Activity (1984) is worth tracking down. Published during the height of the mail art movement it’s regarded as a key work. (See the Sources list [3] for complete publication info and a link to detailed information about the book and the movement.)

Epistolary Books

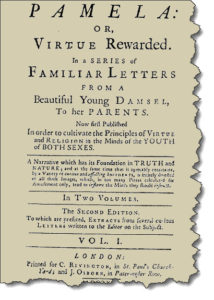

A delightful cousin of illustrated letters is the so-called epistolary novel. The classic is Pamela by Samuel Richardson (1740).

A delightful cousin of illustrated letters is the so-called epistolary novel. The classic is Pamela by Samuel Richardson (1740).

This from Wikipedia details this format succinctly:

“An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of documents. The usual form is letters although, diary entries, newspaper clippings and other documents are sometimes used. Recently, electronic “documents” such as recordings and radio, blogs, and e-mails have also come into use . . . . The epistolary form can add greater realism to a story, because it mimics the workings of real life. It is thus able to demonstrate differing points of view without recourse to the device of an omniscient narrator. An important strategic device in the epistolary novel for creating the impression of authenticity of the letters is the fictional editor.” [4]

Jen Petro-Roy, in their recent article “Writing Epistolary Novels in the Modern Age” (2021) identifying a key aspect of the form that appeals to authors and readers notes that “The form allows for intense emotions while also giving your narrator the option to hold certain details back.” [5]

The format has evolved since the 18th century. The early titles were almost entirely letters. As authors explored the approach the types of communications expanded to include diary and journal entries, newspaper and articles, sections of wills and other legal documents . . . to the modern inclusion of electronic documents such as emails, blog posts, and the like.

The format is not limited to a particular genre. Mystery writer Dorothy Sayers, in her book The Documents in the Case (1930), tells the story via character letters assembled as a kind of dossier. [6]. Speculative SF author Ursula K. Le Guin’s groundbreaking work, Always Coming Home (1985), is comprised of stories, poems, maps, dictionaries, charts, and songs (some with footnotes and journal entries) that interweave the two main characters’ narratives. The first edition of Always Coming Home was packaged in a box that included a cassette recording, “Music and Poetry of the Kesh,” created by Le Guin and collaborator Todd Barton. [7] The magical realism trilogy Griffin and Sabine (1991) by Nick Bantock took the notion of an epistolary story literally: the tale is told via letters (that the reader must remove from the physical pages) and postcards printed to show front and back. [8]

Note: The Wikipedia article cited above provides an extensive list of epistolary works from the 18th-century to the present.

The mixed media aspect of the format, I confess, utterly fascinates me! I have a speculative SF book that is currently backburnered while I try to sort out if, or when, publishing technology will let me create the book I have in mind–my notion for the storytelling needs printed page, loose documents and foldout elements a la Bantock, and audio (and possible visual) recordings a la Le Guin.

Locating Pen Friends

Over the years I’ve enjoyed real and fictional correspondences. I currently have two real ones running using a Google Drive folder as the mailbox. This is in part due to the problematic postal delivery issues in the U.S. at the moment and, in part, due to impatience. Letters for me are very active communications. Unless I am handwriting or typewriting a letter—and the point of that is the delicious reality of creating a physical thing for my correspondent to hold, read, and, in theory, treasure—I like my letters to be quickly sent and received.

The letters illustrated in the Smithsonian’s exhibition are those written, for the most part, between friends. If you are interested in developing a snail mail correspondence, one’s friends–be they family, writing compatriots, etc.—are the place to start. Another place to try is The Letter Exchange which has been running since 1982. And TravelandLeisure.com posted this article in 2020 (video included): These Websites Connect You With Pen Pals Around the World. Searching on the phrase finding pen friends also helps. As with any match-up site, you’ll want to vet for safety.

NOTE: This essay is an updated version of one I originally published on my artist blog, Dante’s Wardrobe.

© J.A. Jablonski 2021. All rights reserved.

ABOUT BOOK THOUGHTS

“Book Thoughts” is an intermittent column within my blog. The essays are not so much book reviews as a book responses. I like to converse with and around the books I read.

HOW TO CITE THIS POST

Jablonski, J.A. (2021, Sept 27). Liza Kirwin | More Than Words. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website).

https://jajablonski.com/2021/09/27/more-than-words/

IMAGE CREDITS

Cover of More Than Words. From the Bookshop.org info page.

Letter Image: Tanning, Dorothea. Dorothea Tanning to Joseph Cornell, 1948 March 3. Joseph Cornell papers, 1804-1986. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Letter Image: Bransom, Paul. Paul Bransom to Helen Ireland Hays, 1943. Helen Ireland Hays papers concerning Paul Bransom, circa 1903-1983. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Cover of Correspondence Art. From Mail Art Chro no logy (website).

Title page of the second edition of Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740). Public Domain image (retrieved from Wikipedia). Version here has been slightly modified with image of torn edge and background color.

SOURCES

Disclaimer: As a Bookshop Affiliate (US only) I will earn a commission if you click through on a book title I’ve linked to and make a purchase.

[1] Kirwin, Liza. (2015). More Than Words: Illustrated Letters From the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. Princeton Architectural Press.

[2] Mail Art-Archive at the Staatliches Museum Schwerin. Collection note. Artists’ Pub website. Accessed on 4 October 2021.

[3] Stofflet, Mary & Michael Crane, eds. (1984). Correspondence Art: Sourcebook for the Network of International Postal Art Activity. San Francisco: Contemporary Arts Press. ISBN: 0931818028. https://www.printedmatter.org/catalog/288/

[4] Epistolary Novel. Wikipedia post. From version last edited on 6 November 2021.

[5] Petro-Roy, Jen. (Updated Oct 8, 2021). Writing Epistolary Novels in the Modern Age. Web article. The Writer website.

[6] Sayers, Dorothy L. & Robert Eustace. (1930). The Documents in the Case. Brewer and Warren.

[7] Le Guin, Ursula K. (1985). Always Coming Home. 2001 edition via University of California Press.

[8] Bantock, Nick. (1991). Griffin and Sabine: An Extraordinary Correspondence. 25th Anniversay Edition (2016). Chronicle Books. | Sabine’s Notebook: In Which the Extraordinary Correspondence of Griffin and Sabine Continues. (1992). Chronicle Books. | The Golden Mean: In Which the Extraordinary Correspondence of Griffin and Sabine Concludes. (1993). Chronicle Books.