Characterization—creating characters—is a regular topic in how-to resources for writers. A recent article on the Masterclass website (Aug 2021) notes that relatable characters are what connects a reader to a story, describing them as an “essential element of fiction writing, and a hook into the narrative arc of a story.” [1] The article instructs one to “follow these character development tips when you sit down to write” and then lists eight familiar elements: establish motivation/goals, create a voice, do a slow reveal, create conflict, provide backstory, make the personality believable, provide a physical picture, and develop secondary characters.

These are good practical tips, but how does one do the preliminary deeper thinking, the emotional work, that grounds the character, that lets them become solid to me, the writer, and ideally to the reader? For me it requires inhabiting the character, becoming an indweller.

In discussing her recent collaboration with actor Ben Miles to write a stage script for the third book of her Tudor trilogy, The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel commented, “For me, writing is a very condensed and lonely form of acting. Everything has to be played out inside my head.” [2] It gets more immediate for Mantel too. She says “I’ve been all of the characters for 15 years. I’ve been in and out of all those bodies and minds.”

Two things strike me in Mantel’s take:

- That the immediate is a kind of intimacy (“in and out of all those bodies and minds” )

- That the writer is an actor, working their way through a tale.

Writing (and acting) go beyond backstory, though backstory informs it. It has to do with listening, really listening, to the characters, to the words (if one is playing a theater role), to the words of the others in the space, whether that space is the book one is writing or a play in which one is performing.

The Importance of Listening

In a 2010 BBC News interview, actor Alan Rickman commented on the importance of listening as an actor: “You only speak because you wish to respond to something you’ve heard . . . . All I want to see from an actor to me is the intensity and accuracy of their listening.” [3]

In 2002 actor Peter Hamilton Dyer provided some rehearsal notes re: the character of Feste, whom he played in a well-regarded production of Twelfth Night at the Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. This production saw successive changes in the cast. At the time Hamilton Dyer wrote these notes, only five actors from the previous go-round had stayed on. Anyone who has been through this knows—and if not, it’s easy to imagine—that adjustments need to be made. Different actors, different interpretations, different directorial notions.

Hamilton Dyer wrote, “This has been very refreshing . . . as we are making new discoveries about the characters.” And how that was done, in one instance, is a wonderfully vivid example of the need to listen and be intensely aware of/tuned into not only one’s fellow actors but the other characters (including one’s own):

“. . . [We] did a useful exercise to help us understand the relationships between the characters. We all stood in a circle, in character, and threw a tennis ball from one character to the next. The way in which you pass the ball to someone else depends on both the nature of your character and your relationship with the recipient. So, if you had very little respect for them, you might throw the ball very hard at them, or perhaps put the ball on the ground for them to come and fetch from you. . . . This exercise was really helpful in helping us understand how the characters interact with each other before we approach the text.” [4]

In the novel I am currently working on (an academic mystery), I am in Mantel’s position: “Everything has to be played out inside my head.” Unlike Rickman, Hamilton Dyer, and Mantel, I don’t have fellow actors on my stage. I am writing and playing all the parts.

Side Stories

I’ve worked out a couple of ways to get at this needed intimacy and listening, however. One is what I refer to as side stories. In a sense I am writing fanfiction (fanfic) for my own novel. The Urban Dictionary defines fanfiction as “when someone takes either the story or characters (or both) of a certain piece of work, whether it be a novel, tv show, movie, etc., and creates their own story based on it.” [5]

Initially the side stories were to hear, literally hear in some cases, the voices of my characters. For instance, I know that one, my so-called maps librarian, an academic with three advanced degrees, is low-voiced and self-defensively brusque, with a dry, wry sense of humor, but also cordial and lighter in speech tones when trusting. But to know that is not the same as hearing it. So I wrote scenes between her and other characters to see and hear how she speaks.

In one conversation she is pushed hard and she pushes back, not always rationally to my surprised amusement, and with a physical voice that is neutrally flat. In another, moved to reveal a deep grief, she lets a work colleague see her cry and reluctantly lets them hold her as she does, and her crying includes squeaks! My alpha reader—she reads everything and simply reacts—said that she could finally hear this person, whereas before she only saw her described.

My other approach to intimacy with my characters is the tried and true method of reading my text aloud. But I take it a step further. When there’s no one around (though if there is I can usually manage to do it in my head), I talk to aloud to them and enact how they might speak back. It’s a version of what some writers may call letting their characters take over. I don’t do that. I only set up a what if and then go improv, talking back and forth and watching what I come up with. Then I shift to another what if scenario and do it again.

This approach helped me find the audio vocal quality of two key characters: a non-binary person whose voice I now hear as a humorously melodious tenor (whereas initially I envisioned them as a somewhat flat-in-tone alto); and an English professor who I knew had an American West drawl but who I now know theatrically drags that drawl out a bit when looking to keep people at arm’s-length while, alternately, letting his voice fall into an unexpectedly sensuous tonality when reading poetry aloud in class or when speaking personally to someone important to him.

Whether my eventual readers hear any of this is, of course, an unknown. But I am encouraged in both of my approaches by two other experienced Shakespearean actors: Harriet Walter and Mark Rylance. Both have long performed The Bard, but now, later in life, both have had the opportunity for new takes on characters.

For Walter the parts were familiar but never allowed to be played by a woman: Brutus (Julius Caesar), Henry IV (play of same name), and Prospero (The Tempest). For Rylance it was the chance to return to a role he’d made profound and dear—Olivia in Twelfth Night—only to find there was more to be discovered.

Inhabiting

The notion of intimacy, of inhabiting, is vivid in both of their descriptions. Walter found herself silencing her personal speaking and interaction styles by listening to the characters, some of whom she might have played opposite to earlier on. She inhabits by finding something within these male roles: “For these three roles, I discovered that power comes from stillness, from not giving anything away. All the things that I tend to do as Harriet – hand gestures, speaking a good deal – all that, gone.” [6]

Rylance found a similar minimalism in occupying the woman Olivia. A double viewing of Kabuki actor Tamasaburo in an old Japanese drama, once from the cheap seats and the next in row three, gave him an insight into how Olivia might be played effectively with “powerful reserve.” [7] Playing her at The Globe, where the audience is such a vibrant part of the performance (something Hamilton Dyer has commented on as well) and where listening to the audience as participant is key, gave Rylance additional notions as to how he might add nuance. A later, tragic experience (the unexpected death of Rylance’s stepdaughter Nataasha) turned Rylance inward, to a listening to Olivia herself. He commented, upon returning to rehearsals with long-time colleagues,

“These characters, when you play them again, it’s really like meeting an old friend. And there Olivia was kind of saying to me, ‘Now you know what I feel.’” [7]

There is nothing original to this notion, that one must listen and inhabit. All fiction writers are, perforce, actors. Like Mantel, they play things out inside their heads. But for myself and my characters, I’ll leave some last words to Rylance, words that have honed my awareness and enlivened my own sense of immediacy for words and creating:

“Backstage,” he says, “I always have one ear to the house, judging the energy of the audience from their response to other scenes, enjoying the innovations and discoveries of my fellow actors, and privately harnessing the aspects of myself, the thoughts and actions, that are appropriate for my character.” [8]

© J.A. Jablonski 2021. All rights reserved.

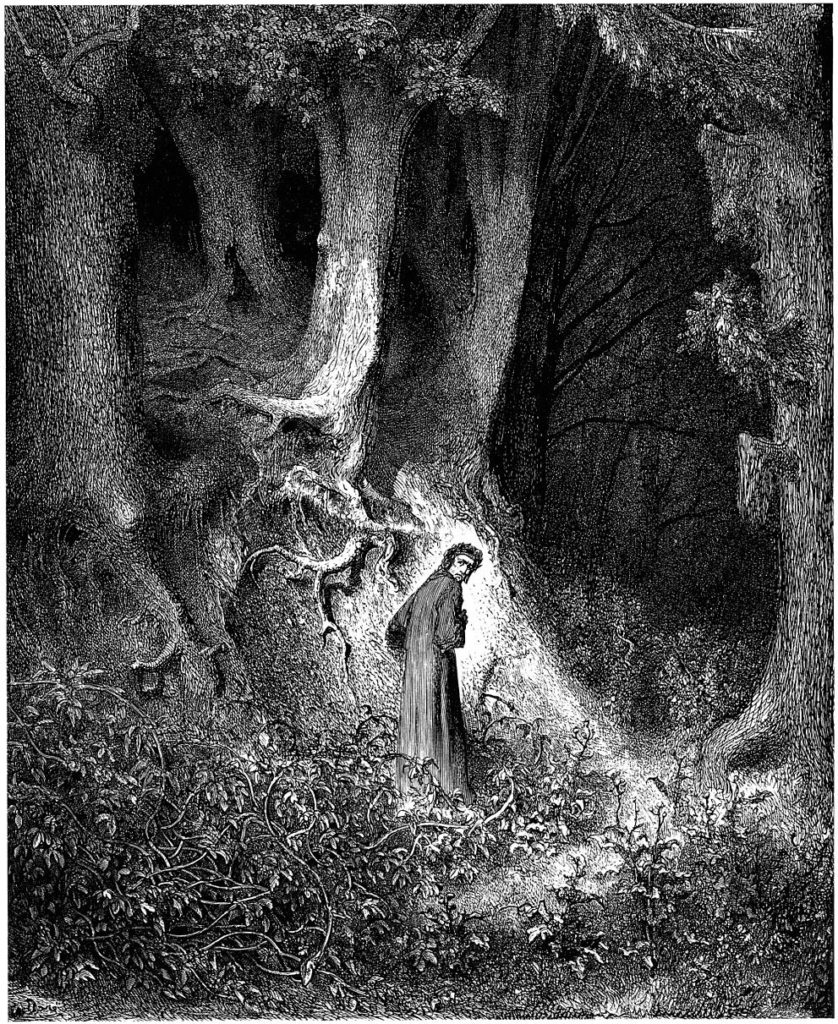

Now, as Dante put it at the beginning of his

Now, as Dante put it at the beginning of his I’ve read many children’s books and, as I began this post noting, many notable works of imaginative fiction. And I am a rather angry reader as a rule. That is, it doesn’t take much for a book to lose my interest or respect. As a former English teacher and theater major, and long-time information professional

I’ve read many children’s books and, as I began this post noting, many notable works of imaginative fiction. And I am a rather angry reader as a rule. That is, it doesn’t take much for a book to lose my interest or respect. As a former English teacher and theater major, and long-time information professional Immediately upon reading the first page, my hackles twitched. I could hear hobbit and hitchhiker’s guide and all manner of many coy literary allusions. But something Vernon does, and does very well, managed to deflect my inner critic.

Immediately upon reading the first page, my hackles twitched. I could hear hobbit and hitchhiker’s guide and all manner of many coy literary allusions. But something Vernon does, and does very well, managed to deflect my inner critic.

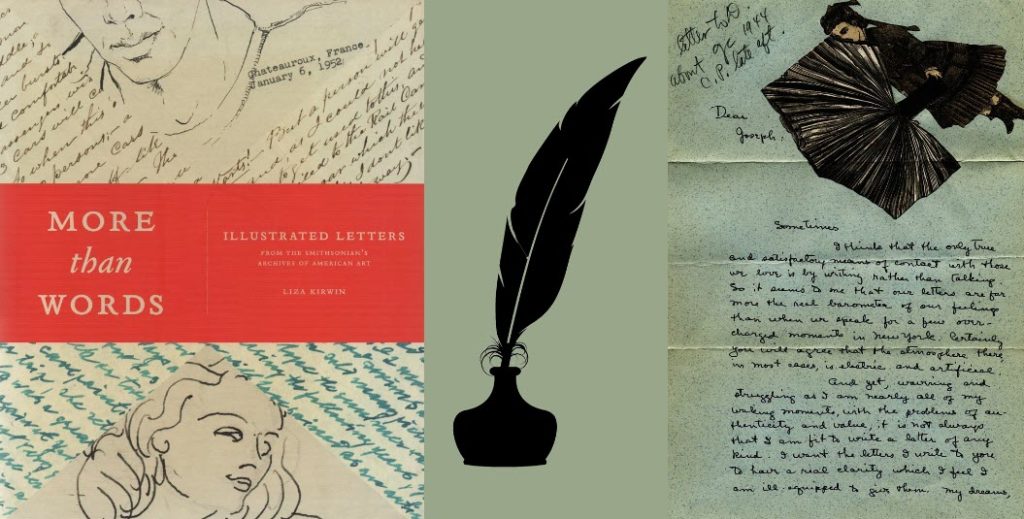

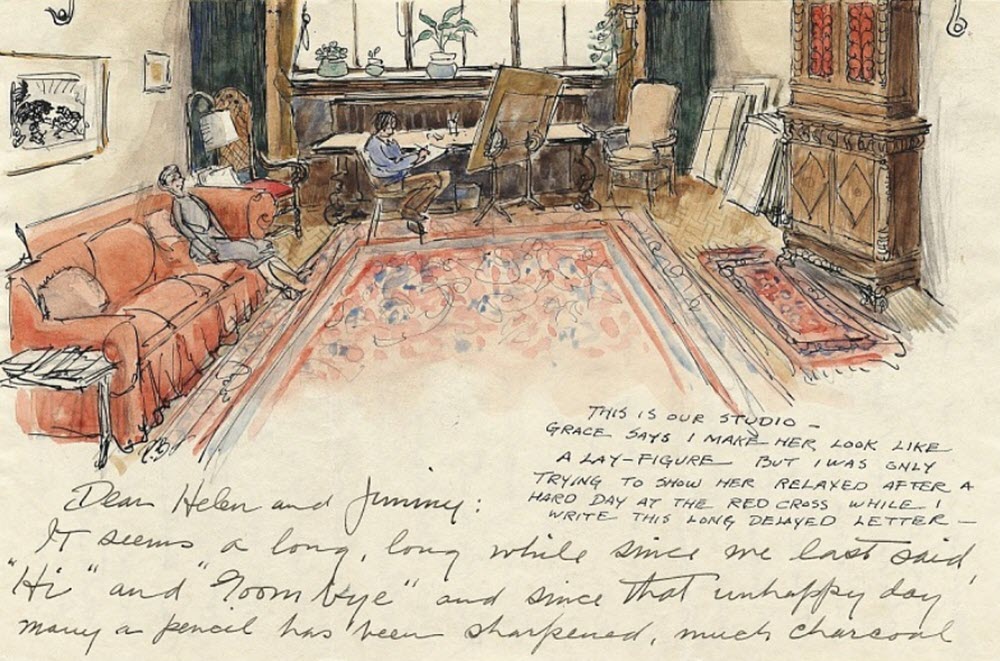

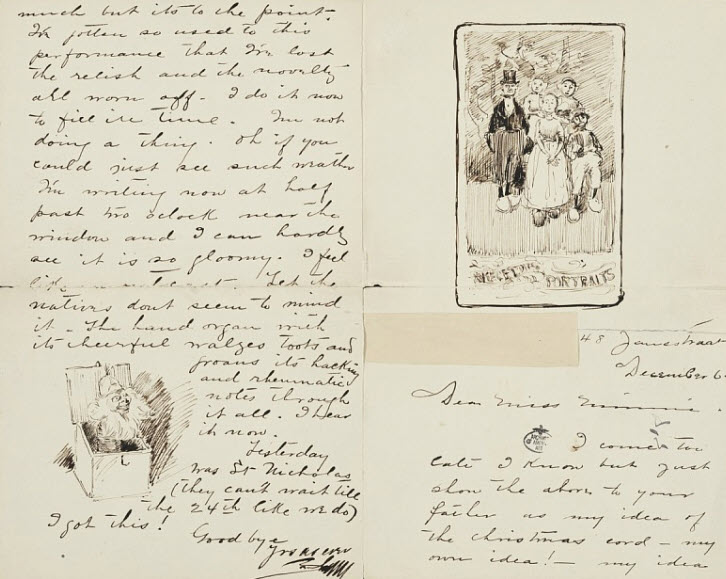

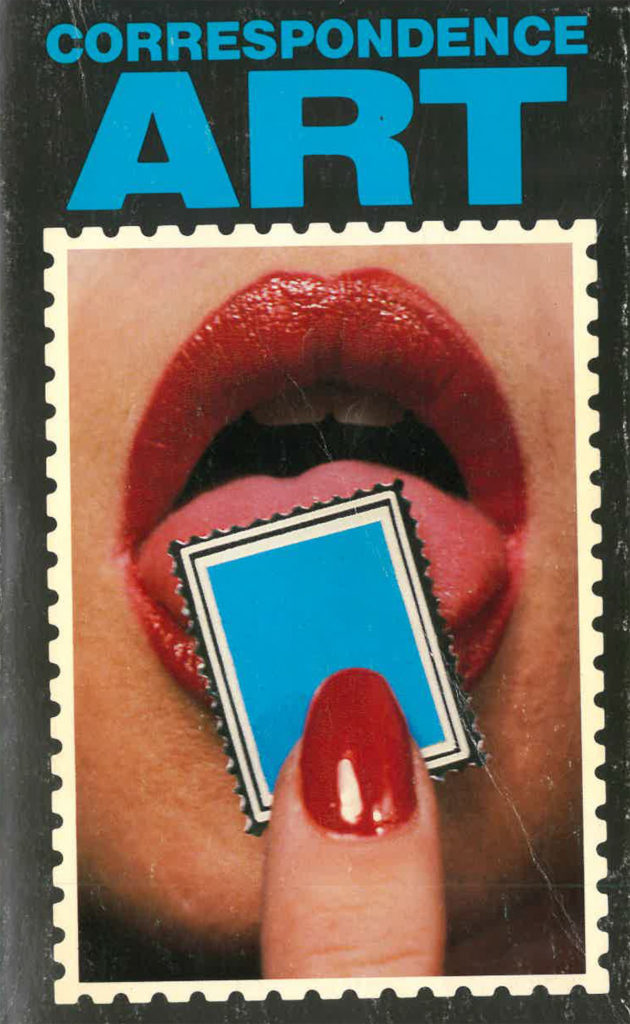

The final paragraph of the Introduction urgently notes the loss of these material treasures that are “all but disappearing from our culture.” I am less convinced that this is so. The

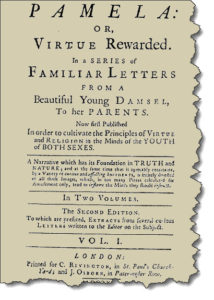

The final paragraph of the Introduction urgently notes the loss of these material treasures that are “all but disappearing from our culture.” I am less convinced that this is so. The  A delightful cousin of illustrated letters is the so-called epistolary novel. The classic is Pamela by Samuel Richardson (1740).

A delightful cousin of illustrated letters is the so-called epistolary novel. The classic is Pamela by Samuel Richardson (1740).

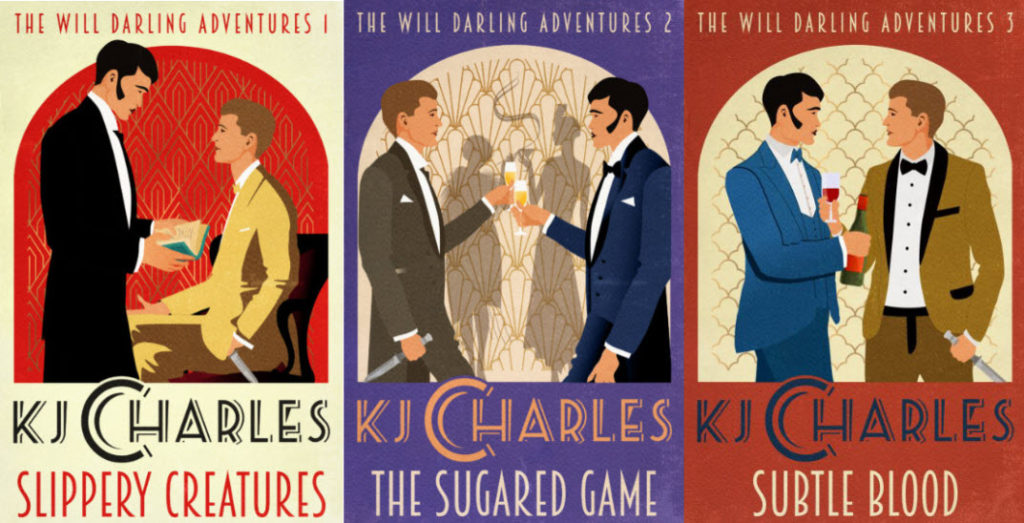

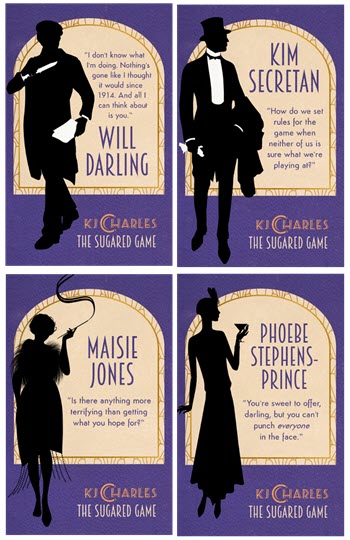

The story opens with Will taking best friend Maisie to the High-Low Club for an evening on the town. The club is glamorous but seedy, clearly a haven for nefarious doings of all sorts. It becomes the focus of the plot and the continuously fractured romance between Will and Kim. While at the club Will meets a one-time military compatriot. Kim, who initially is as unreliable, and irresistible, makes use of Will’s connection, turning the bookseller’s finally neatened world into one more secretive, criminal, and underhanded.

The story opens with Will taking best friend Maisie to the High-Low Club for an evening on the town. The club is glamorous but seedy, clearly a haven for nefarious doings of all sorts. It becomes the focus of the plot and the continuously fractured romance between Will and Kim. While at the club Will meets a one-time military compatriot. Kim, who initially is as unreliable, and irresistible, makes use of Will’s connection, turning the bookseller’s finally neatened world into one more secretive, criminal, and underhanded.