“It tickled me that while I knew a certain thing had to happen, because that’s the trope or literary tradition Parry was representing, how she twists the representation into a unique thing is what makes it her story—which is precisely how literature works.”

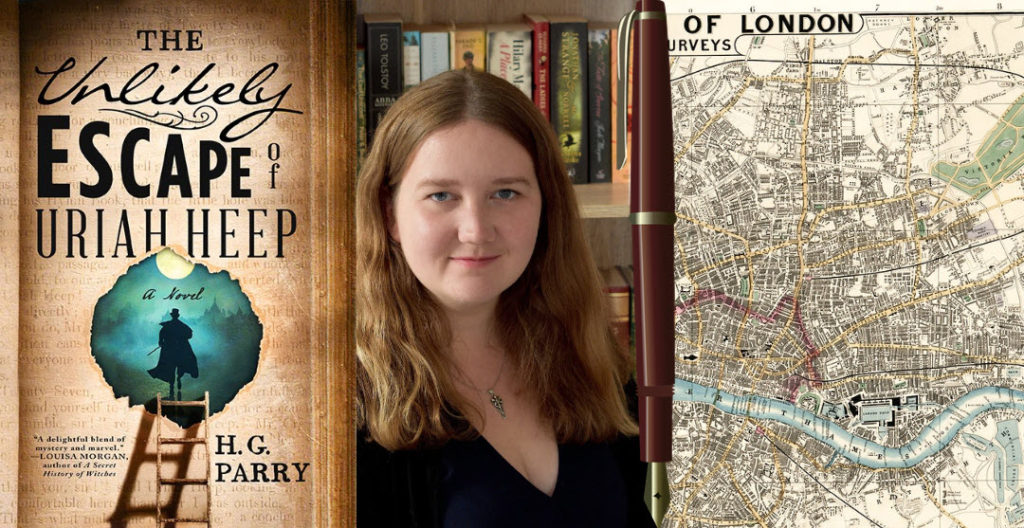

H.G. Parry’s The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep (2019) is a delightful, splendid, maddening, curious, detailed, remarkable, tantalizing, intriguing, distancing, overexcited, cheering, and rewarding book. Pieces of it turned up in my dreams immediately after I finished reading it. This only happens if something—person, place, thing, or event—has done something unequivocal to me and my imagination. [1]

The dream pieces were partial images, those I recall seeing as I read but, as within Heep, disappeared and reappeared sporadically. There were a lot of words flying about, differently sized and mostly in serif font. (I think the cover of the book may have had something to do with that.) And there was a quality of light to most of the dreams which was unexpected, a kind of hovering glow of gold satin.

It is an unusual book.

THE STORY

First, the description of the story from Parry’s website:

For his entire life, Charley Sutherland had concealed a magical ability he can’t quite control: he can bring characters from books into the real world. His older brother, Rob—a young lawyer with a normal house, normal fiancée, and an utterly normal life—hopes that this strange family secret will disappear with disuse, and he will be discharged from his life’s duty of protecting Charley and the real world from each other. But then, literary characters start causing trouble in their city, making threats about destroying the world . . . and for once, it isn’t Charley’s doing. There’s someone else who shares his powers. It’s up to Charley and a reluctant Rob to stop them, before these characters tear apart the fabric of reality. [2]

The Difficulty of fiction

Getting into the book was an odd experience. Reading fiction is hard for me, magical realism even more so. My academic training had a goodly component of literary analysis. I did a large piece of research that involved heavy duty content analysis. Then I went on to teach writing and literary analysis for a time, and after that did and taught book and database indexing which requires that one objectify text in order to label its contents for intellectual access.

As a reader, I find it exceedingly difficult to turn off these various aspects of my mind that run at full tilt most of the day. This means reading is never simply that. Add to that fun, I am a long-time writer. The bulk of my career was professional writing with the occasional self-expressing poetry or fictional correspondences as private entertainment. For the last five or six years I have been writing fiction: magical realism, speculative fiction, and academic mystery. [3]

What is so fun about Parry’s book is that none of this mattered while at the same time it thrummed below like a bagpipe’s drone all the while I read.

And none of this is needed to enjoy The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep. It’s a fulsome, fat book that reads fast and fun and goes on and on.

IMPRESSIONS

Some thoughts on the book.

Heep takes a little time to get going. Older brother Rob is a bit of a pill in terms of personality. He has the arrogant know-it-all ways of an older sibling and Charley is a bit whiny at first to my tastes. Frankly, I found them both annoying but decided to give Parry benefit of the doubt. Also, analytical-me could see she was doing something. Who, what, and how these brothers are matters.

Parry has her own interesting take on their creation:

Charley because he’s seen mostly through other people’s eyes, so it was difficult to sift through that and see who he really is inside his own head; Rob because he’s so reluctant to get involved with anything outside the norm that he risked missing out on most of the plot! [4]

Once the actual adventuring begins the story takes off. Millie Radcliffe-Dix—a girl detective of Parry’s invention who is a bit of a mix of Nancy Drew and Pippi Longstocking—provides a strong, to my mind stronger, counterpoint to Charley than his brother. When Millie is on stage things seem more coherent. Then again, that is her role and the literary notion of role is central to the characters (those real and those read-in) to the plot, and to the larger tale Parry is creating.

Sherlock Homes by Sidney Paget

Jane Austen (based on sketch by her sister Cassandra)

Charles Dickens (From the National Library of Wales)

Characters and creatures begin to appear, seemingly at random at first: Uriah Heep (from David Copperfield) running around Charley’s English Department and a most fiercesome and real Hound of the Baskervilles (from Conan Doyle’s book of the same name) attacking the brothers at Charley’s home. Then their authors start popping up and other authors, or their representations (there are multiple versions of Jane Austen’s Mr. Darcy, each manifesting a certain, different trait of the man as Austen wrote him). Dickens’ Dorian Gray is quite the devious charmer who both moves the plot onward while providing a seething uncertainty beneath the action.

There are coexisting universes, not unlike the mundane reality of a reader and the imagined reality created by the book she is reading. The shifting between the two is puzzling at first—I found myself wishing the book’s editing had been slightly tighter here as the imagery was a bit overwhelming (for me, that is). But the increasing overlap of space, places, and imagination becomes a necessary element of the plot and the story.

It’s difficult to describe further as it might compromise a reader coming fresh to this delightful book. I can say the ending was charming while also satisfying. Somewhere I read that Parry has been asked about writing a sequel and I don’t see how she could without simply repeating herself. A sequel would simply rerun the tropes and story types she has broken apart this once and so successfully. There were some minor characters, some needed for the plot, some for a kind of comic sensibility, that I’d have edited out, but they do work. (I suspect that’s my English professor persona having a small fit.)

All in all, The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep is a book I will want to periodically reread, which I don’t often do unless something about the book took joyous hold of my imagination.

The personal book

I know I am not the only person who felt this but it seemed Parry wrote this book just for me, the one-time academic and academic librarian, the double English major, the been-reading-since-I was-three person. I got to use all my skills and training in cahoots with someone whose skills and training are enough above mine to make reading Heep a sort of game. Could I anticipate a certain next part of the story? Yes! Did I see the occasional inside literary joke? Yes! Did I know the ending because of what I know about how literature, criticism, and storytelling work? Yes.

But even better, not yes.

I knew what was going to happen pretty much all the way through because a close reading of the characters—the literary persons that exist or appear throughout the story and the characters that made the story itself—meant only certain things could happen. So although I knew X would happen or a certain person would do or be something/someone, it didn’t happen quite as I thought it might. I felt genuine childlike glee every time it happened as though Parry and I were playing a game of badminton tapping the birdie back and forth. I got to be Charley (!) who early on explains what reading is for him:

And while I am reading, the new words I’m taking in will connect to others I’ve already taken in . . . . They make a map, or a pattern, or a constellation. Formless, intricate, infinitely complex, and lovely. And then, at once, they’ll connect. They’ll meet and explode. Of course. That’s the entire point! That’s how the story works, the way each sentence and metaphor and reference feeds into the other to illuminate something important. That explosion of discovery, of understanding, is the most intoxicating moment there is. Emotional, intellectual, aesthetic. Just for a moment, a perfect moment, a small piece of the world makes perfect sense. And it’s beautiful. It’s a moment of pure joy, the kind that brings pleasure like pain. (pg. 26)

A page later Charley says,

That part is the magic, in that it’s a step further than most people’s reading or analysis goes. It all feels one and the same to me, but that’s where the line crosses from the accepted to the extraordinary. (pg. 27)

But for all that my lit crit and writing background had me primed, Parry often caught me off guard, often in the most wonderful ways. I won’t spoil anyone’s reading with specifics (and there are many opportunities for this). It tickled me that while I knew a certain thing had to happen, because that’s the trope or literary tradition Parry was representing, how she twists the representation into a unique thing is what makes it her story—which is precisely how literature works.

And why writing fiction is so hard! Writers are told to “be original” while also being told that, fundamentally, there are only seven types of stories. [4] So how does one manage? How does one make a type fresh?

In Parry’s case, it was a matter of taking that other adage—write what you know—and converting it to write how you know. About half way through Heep one of the character-people tries to explain something to Rob by saying “If you were in a certain kind of book . . . .” Parry, the writer with a PhD in English Literature, does a version of this. It’s as if she instead asked herself If I were a certain kind of book . . . .

In a 2019 interview, when asked what research did for this book she said “I cheated with this, because I deliberately wrote a book about everything I love and so I knew a lot already.” [5]

It must have been quite freeing to simply cut loose in a way that both honored the breadth and depth of English Literature as a formal field of study while also, in effect, kicking all the formal requirements of literary criticism and analysis right in the teeth.

Left: The Lady of Shallot by William Holman Hunt

Right: Penelope and the Suitors by John William Waterhouse

The fun I had with Heep has made my years in academe and lit crit so worth it! Witty, heartfelt, & just plain delightful. Parry is not simply a story teller, she is a story weaver: Ariadne unwinding her skein; The Lady of Shallot embroidering images seen in her mirror; Penelope weaving and unraveling her father-in-law’s shroud. She plays, deeply plays, and we and our imaginations are the better for it in so many ways.

If you have a question or comment for me, drop me a line via my Contact page.

© J.A. Jablonski 2022. All rights reserved.

ABOUT BOOK THOUGHTS

“Book Thoughts” is an intermittent column within my blog. The essays are not so much book reviews as book responses. I like to converse with and around the books I read. Sometimes I will write more formally, sometimes off the cuff, sometimes almost intimately. I write about what I feel like writing about. A book might have come out a month ago, a few decades ago, or a few centuries ago. I read as I please and when thoughts about the experience come to mind sufficiently, I write them here.

How to cite this post

Jablonski, J.A. (2022, June 8). H.G. Parry | The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website). https://jajablonski.com/2022/06/08/parry-uriah-heep/

IMAGE CREDITS

Header image

-

- H.G. Parry author photo. From her website.

- Cover of The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep. From Parry’s website.

- London Map. Whitbread’s new plan of London: drawn from authentic survey (1853) by J. Whitbread. From RawPixel.com.

Sherlock Holmes by Sidney Paget. Via Wikipedia.

Portrait of Jane Austen, from the memoir by J. E. Austen-Leigh (1798-1874). Via Wikipedia.

Charles Dickens. From the National Library of Wales. Via Wikipedia.

The Lady of Shallot by William Homan Hunt. Via Wikipedia.

Penelope and the Suitors by John William Waterhouse (1911-1912). Via Wikipedia

SOURCES & NOTES

Disclaimer: As a Bookshop Affiliate (US only) I will earn a commission if you click through on a book title I’ve linked to and make a purchase.

[1] Parry, H. G. (2019). The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep. Redhook.

[2] H.G. Parry’s webpage for The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep.

[3] See this section of my website for a rundown of my works done and in progress.

[4] The Quillery. (2019, July 30). “Interview with H.G. Parry, author of The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep.” The Quillery website.

[5] Booker, Christopher. (2004). The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. Bloomsbury Continuum. (This link is to the 2019 edition.)

[6] The Quillery. (2019, July 30). “Interview with H.G. Parry, author of The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep.” The Quillery website.