“We understand in this painting what is round, flat, or soft.

We get a tactile sense of the textures, how they feel, by studying the painting.“

Earlier this Fall while touring the Minneapolis Institute of Art I came upon Kenneth Schweiger painting a copy of Henri Lehmann’s Portrait of Clémentine (Mrs. Alphonse) Karr, 1845. I’ve seen people doing this in other art museums but in this case was struck by the quality of Schweiger’s work and his ease in talking about it. I wanted to hear more about his creative way of thinking and the practical logistics of what he does so I asked him if we might continue our conversation in an interview here.

BIO

Kenneth Patrick Schweiger is a Fine Artist in St. Paul, MN (USA). He also serves as an Instructor at The Atelier Studio Program of Fine Art in nearby Minneapolis. Schweiger attended DePaul University in Chicago, IL. After graduation, he lived in Tokyo, pursuing his interests in Japanese art and culture.

JAPAN

JAJ: I am intrigued by your fascination with the art of Japan. What first drew you to Japan after your studies at DePaul?

KS: I visited Nagasaki the summer between my 2nd and 3rd year in high school. It was my first international travel experience and the influence was profound. I took a Japanese Language class at DePaul initially as a graduation requirement. After the first semester, I was excited and motivated to continue pursuing art and Japanese.

Growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, Japanese culture permeated our sources of electronic entertainment in the United States. Nintendo and Super Maria, Sega and Sonic the Hedgehog, Voltron. These cultural exports were tremendously inspiring. It was not until my teens and early 20s that I was able to connect them with the country of Japan.

I also grew up reading and enjoying Marvel and DC comics—particularly X-Men and Batman—as Saturday morning and after school cartoons showcased these characters. When deciding my career goals, I had an inkling that it was to write stories via comics. Comics, and now graphic novels show a tremendous visual experience. Pictorial compositions explain the words; the words explain the pictures. It was a glorious calligraphy of shape and line.

I also grew up reading and enjoying Marvel and DC comics—particularly X-Men and Batman—as Saturday morning and after school cartoons showcased these characters. When deciding my career goals, I had an inkling that it was to write stories via comics. Comics, and now graphic novels show a tremendous visual experience. Pictorial compositions explain the words; the words explain the pictures. It was a glorious calligraphy of shape and line.

At DePaul, while I floundered to declare a major, the university newspaper accepted an illustration in my freshman year. I drew comics for four years there under the mentorship of an illustrator named Brian Troyan and an editor named Will Moss. Will Moss is now an editor at Marvel Comics. While drawing comics and studying Japanese, a textbook entitled Mangajin’s Basic Japanese through Comics delivered a decisive, life course altering impact. [1] I read this glorious text over and over during my college summers, when not driving a forklift at my summer work gig. In this Rosetta Stone-like manual, Japanese and English were placed side by side with comics. Words I understood and attractive pictures set alongside words I was struggling to understand. It was a door-opening portal whose rewards plunged me into a new world of cultural norms, and expectations. The art forms, the pictorial language had the savor of childhood nostalgia and yet was more.

JAJ: In a 2022 interview you said of the art you saw in Japan that “There was a mysterious quality about that work that I wanted to participate in and be part of.” [2] Can you speak more about that quality and what and how “being a part of it” means?

KS: I am fascinated by the woodblock print designs of the Edo period. The Great Wave over Kanagawa, from Hokusai’s 36 views of Mt. Fuji is a stellar example. [3] The compositions are magnificent. The shapes, colors, and tonal masses are balanced. The line work is exquisite. I find them to be poetic representations of life at that time.

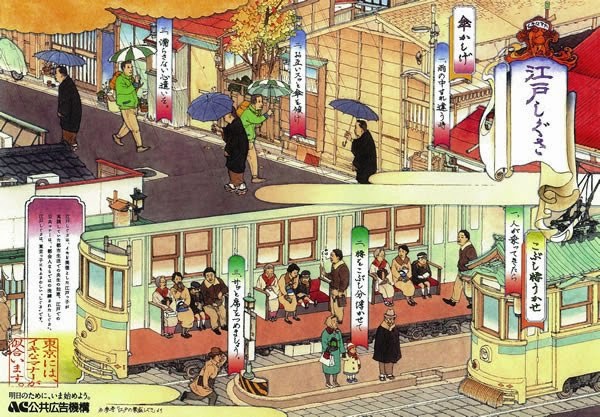

My residence in Japan was permitted by a work visa acquired through an English teaching corporation. I worked at elementary and junior high schools in the Bunkyo ward as an Assistant Learning Teacher supporting English teachers and providing native examples. I was riding the subway in Tokyo in 2007 and noticed an ad campaign by the metropolitan government entitled Edo Shigusa or Old Tokyo’s Manners. [4]

It depicted passengers on a streetcar sliding over to make room for another to sit down. There were multiple versions, people turning their umbrellas while passing on a crowded sidewalk, etc. The style looked like a Hokusai print. Yet the characters mingled period dress with cell phones, suits, and ties—it was a seamless blend of past and present. I had to find the artist. His name is Yamaguchi Akira, and he is a contemporary fine artist working in Tokyo, and represented by Mizuma Art Gallery near Shinjuku. [5] Seeking out his art shows in galleries put me in pursuit of this mysterious quality. I think it may be a canon of pictorial forms in Japan.

JAJ: You recently co-lead a Small Group Journey on the “Textile and Traditional Arts of Japan” that saw you visiting several cities. The itinerary was fairly elaborate! [6] What was your role? Did you help plan the tour?

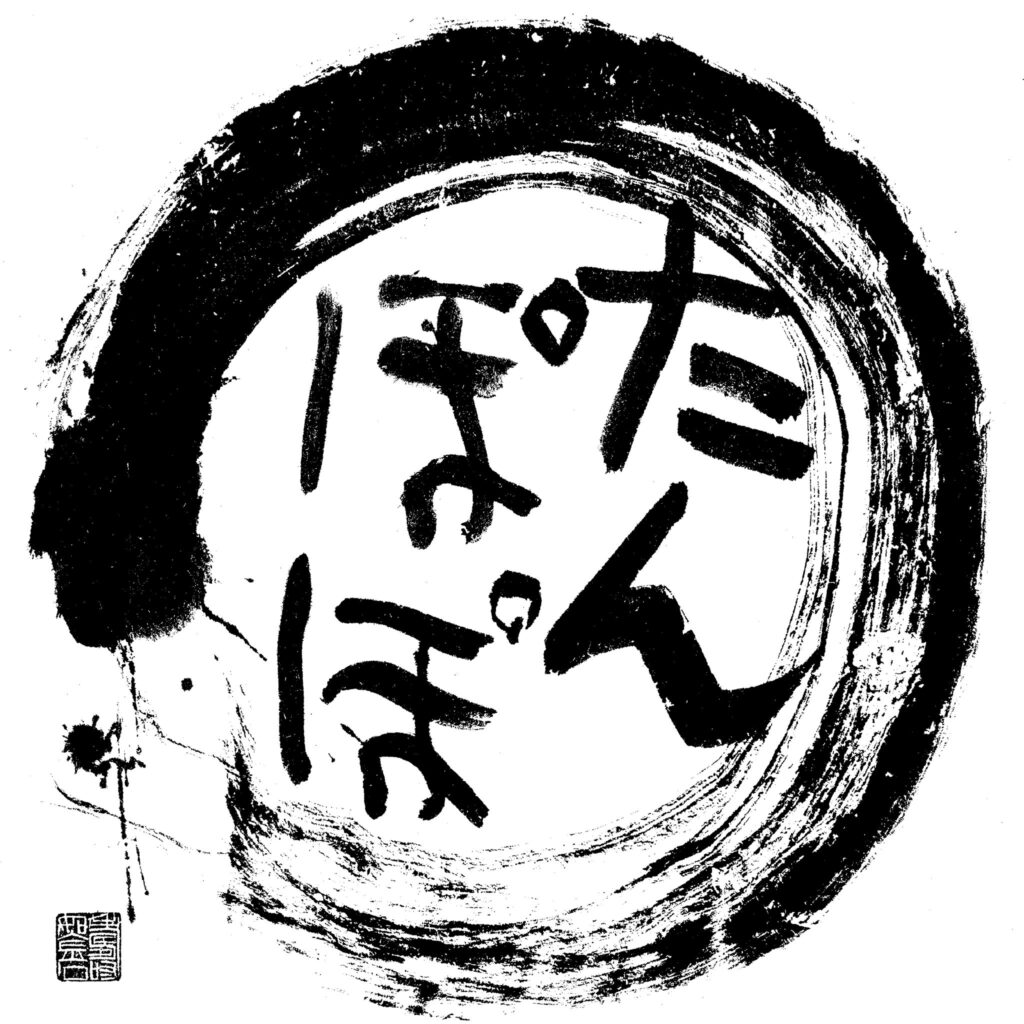

KS: My role was in assisting the founder of Tanpopo Journeys, Koshiki Yonemura, with guiding guests on the workshop visits, translating language and cultural questions, and navigating the train system.

Koshiki had been my boss at a Japanese noodle restaurant in Lowertown Saint Paul called Tanpopo Noodle Shop. She, her husband Ben, her mother, and brother Ira, as well as an incredible, tightly knit team of kitchen and serving staff operated Tanpopo at a standard of excellence that drew me back multiple times to eat delicious soba and udon noodles.

Koshiki had been my boss at a Japanese noodle restaurant in Lowertown Saint Paul called Tanpopo Noodle Shop. She, her husband Ben, her mother, and brother Ira, as well as an incredible, tightly knit team of kitchen and serving staff operated Tanpopo at a standard of excellence that drew me back multiple times to eat delicious soba and udon noodles.

After about the 3rd visit, I had to turn in an application and worked as a server there. I served evenings from Thurs ~ Saturday, which connected me to the Lowertown Arts Community. We would finish our shift at 9 or 10pm, slurp an amazing bowl of udon, and walk over to Saturday night jazz at the Black Dog Cafe. Concert musicians played together on that stage from around the metro area, nation, and internationally, for tips! One beer, live music, and a community of working artists formed a very constructive artistic environment.

In a simple way, I was maintaining a connection to Japan. But I felt that if I was to grow beyond teaching English, and wanted to produce higher quality artwork, I needed help. At around 2011/12, I began taking a night class in northeast Minneapolis in a studio called the Atelier. [7] The content of the class was pure drawing. We arrived, set up an object to draw, and worked on one drawing for 14 weeks. I left with blurry eyes, frustration, and a growing ability to draw well. It fed my soul, and was to become a pathway to full time study of classical methods of drawing and painting.

THE ATELIER

JAJ: You mention in your Artist Statement that your work draws on the atelier tradition. What is it about the atelier approach that calls to you as an artist? And further, how do you translate that tradition to your students?

The Atelier tradition in America goes back to the Boston School, a group of American painters in the late 19th century that traveled to Paris to study oil painting. Painters like William Paxton, and Thomas Eakins made the transatlantic journey to study in the ateliers (French for workshop) of renowned French artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, Léon Bonnat, Alexandre Cabanel, and William Bougeureau (see the “Carpet Merchants” at the Minneapolis Institute of Art). [8]

This teacher to student transmission of knowledge includes intense study of classical sculpture via cast drawing and cast painting. Along with learning to see, daily drawing and painting from a live model, as well as still life painting develops a student’s ability to see visual information and translate it accurately onto paper or canvas.

JAJ: This may seem like an odd question, more likely an ignorant one! When I read up about the atelier tradition certain aspects of it struck me as almost rigid. It’s not copying per se, but there it seems there is a creatively finite quality to realism. Does it seem that way to you?

KS: This is an excellent question that is hotly debated. I chose the atelier tradition because it has equipped me with the tools to develop my artistic vision and a method to express it. When I lived in Tokyo, and intuitively tried to sketch either from life on the street or from examples in books, I could not replicate the lines and shapes. Not only that, I could not see or figure out the gap between the two. It was humbling! I needed the guidance of a skilled teacher to first open my eyes. And it wasn’t solely a function of my eyeballs, but also a development of the mind, heart, and hand to a more subtle, sophisticated translation of what we think we see. When that understanding unfolds onto paper or canvas, this can be described as the language of art.

The thread of human figurative art that weaves through Ancient Egypt, Greece, Roman art, the Italian Renaissance, and the French Salon are irresistible. The best of it is so profoundly beautiful, and the paragons of this tradition are steeped in learning from our predecessors. The more I make copies of past great work; the more I appreciate its wonder. I would make a musical analogy, great piano and violin players are encouraged to practice scales and learn Mozart before attempting to compose a symphony. I feel a similar way about drawing from Michaelangelo or Cabanel.

THE PORTRAIT OF CLEMENTINE

JAJ: Henri Lehmann’s Portrait of Clementine is a dramatic painting and stands out among the other works in the MIA gallery. Were you looking for something in particular when you saw her? Or was there something about her specifically that made you want to paint her? [9]

KS: The Portrait of Clementine is a world class masterpiece of oil painting. It is strikingly naturalistic; as if a woman put on a dress, styled her hair, and sat down on the other side of the window. It is also composed expertly—the perspective, light source, and arrangement of light and dark shapes are well balanced. The oval frame echoes the shapes within the portrait.

Lastly, the technical layering of colors is done with a deep and thorough understanding of oil paint. There are subtle green color notes within the forehead that could not have been painted directly on the surface layers. They emerge from within gently giving dimension to the forms of the brow, eye socket. There are bright orange/red accents within the shadows at the nostril, and upper lip. This leads me to believe that some of the underpainted layers are being allowed to show through a semi opaque veil.

JAJ: How long have you been working on this painting? Do you have to be in the museum in front of her or can you work on it in your personal studio?

KS: I began painting on Clementine in August of 2021. I did a grisaille or grey scale painting to prepare the canvas in my studio. [10] From there, all color work was done in front of the painting at the museum.

JAJ: At one point when we were talking in the museum, you pointed to Clementine’s forearm, just below her bracelet. You spoke of the softness of the color along the line of light and Lehmann’s careful brushstrokes. You wanted to capture that. As a writer I would compare that to reading a certain author and noticing a specific quality in their writing that I might want to imitate or echo. Is this what you meant by “capturing?” Is it a matter just of technique or something else, something more? What or how do you think when you “capture?”

KS: Yes absolutely! Ted Seth Jacobs, an American painter, once said he does not teach technique when drawing. He asks students to carefully express what they understand about a person’s face or body in a drawing, and technique is born from that search.

I wanted to catch a glimpse of Lehmann’s form sense. He expressed an idea about the sensual quality of her arm, skin, hair, and dress, and said it in paint. We understand in this painting what is round, flat, or soft. We get a tactile sense of the textures, how they feel, by studying the painting. We also feel the presence of a specific person in this picture.

Kenneth Schweiger can be found online here:

-

- Website

- Artist Statement

- YouTube Interview: THE ARTIST STOOL | KENNETH SCHWEIGER | PAINTER (January 31, 2022)

- Studio & Contact Info

If you have a question or comment for me, drop me a line via my Contact page.

© J.A. Jablonski 2023. All rights reserved.

ABOUT ten toes interviews

Ten Toes Inverviews is an intermittent column in which I talk with creatives of all sorts. The interviews are collaborative. Read more about them here. (I am looking for people to interview. Please drop me a line via my Contact page with your ideas.)

How to cite this post

Jablonski, J.A. (2023; Feb 21). Ten Toe Interview: Kenneth Patrick Schweiger. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website). https://jajablonski.com/2023/02/21/interview-kenneth-patrick-schweiger

IMAGE CREDITS

Kenneth Schweiger painting Lehmann’s Portrait of Clémentine in the Minneapolis Institute of Art in October 2022. Photo by J.A. Jablonski (All rights reserved).

Portrait of Kenneth Schweiger. Image provided by Mr. Schweiger.

Mangajin’s Basic Japanese through Comics. Book cover. From Japanese Quizzes website.

“Edo Shigusa or Old Tokyo’s Manners.” From the Neko Jitablog. (2015-02-11).

Tanpopo Journeys Logo. From their Facebook page.

Kenneth Schweiger’s version of “Portrait of Clementine” in front of the original painting by Lehman at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Photo by J.A. Jablonski (All rights reserved).

SOURCES | NOTES

[1] Mangajin’s basic Japanese through Comics : A Compilation of the First 24 Basic Japanese Columns from Mangajin Magazine. (1998). Weatherhill. ISBNS: 9780834804524 & 0834804522. WorldCat record.

[2] Episode 001 of “The Artist Stool” interview (YouTube, 2022).

[3] 36 views of Mt. Fuji. (1760–1849). This Wikipedia article displays the images.

[4] Edo Shigusa or Old Tokyo’s Manners. A 2015 article in the Japan Times cites a page from the “government-approved morals education textbook “Watashitachi no Doutoku” (“Our Morals”), for fifth- and sixth-graders, [that] describes behaviors said to be from the Edo Period.”

A search for that textbook brought up this interesting article: Unsriana, Linda & Ningrum, Rosita. (2018). “The Character Formation of Children in Japan: A Study of Japanese Children Textbook on Moral Education (Doutoku).” Lingua Cultura. 12. 363. 10.21512/lc.v12i4.4270. It can be read in full at this link.

[5] Yamaguchi Akira. Artist. His information page at the Mizuma Art Gallery.

[6] The latest itinerary for this tour can be found at this link.

[7] The Atelier Studio Program of Fine Arts. 1621 East Hennepin Avenue, Suite 280

Minneapolis, MN 55414. Website.

[8] More on the artists Schweiger mentions can be found here. The detail and quality of the information in these Wikipedia articles varies. Some, but not all, include links to collections that hold the artist’s work(s), exhibition catalogs, and external links to research articles and/or websites.

[9] A brief article on Henri Lehmann can be found on Wikipedia. More of his works can be seen at the ArtNet website here.

[10] As Schweiger notes, a grisaille is monochromatic painting in shades of gray. This article by Scott E. Bartner shows the step-by-step progression from a grisaille to a complete work. (“Working Up from a Grisaille.” (n.d.) Artists Network website.)