Character Morgues: Finding Faces

“The face is the mirror of the mind,

and eyes without speaking confess the secrets of the heart.”

~ St. Jerome

As part of my writing practice I create character morgues. At the beginning of a story I usually have only a general notion of what my people look like. Having more specific images helps me work out not just how they look but their psychology and their backstory. The idea for morgues came from my college days.

Undergraduates are famous for changing their majors and I was no different. I started out in theater because the most fun I had in high school was working on the school plays. I eventually ended up getting the BA in English Literature, but those first months crawling around the university’s theater building remain among my best memories.

The stage makeup class is something I still look to as a writer. We had to create a makeup morgue, a collection of pictures and photographs of examples people of various ages, unusual makeups, and hairstyles. They could be modern images or historical. The morgue served as your personalized reference book that helped you envision your characters’ look and makeup.

Sample morgue images

To find pictures for my morgue I often use Google Images, Unsplash, and Tumblr.

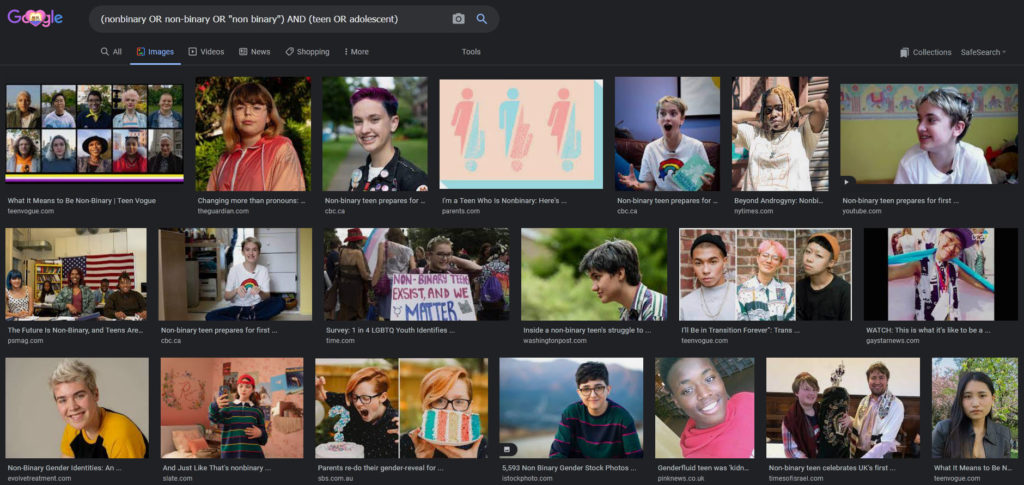

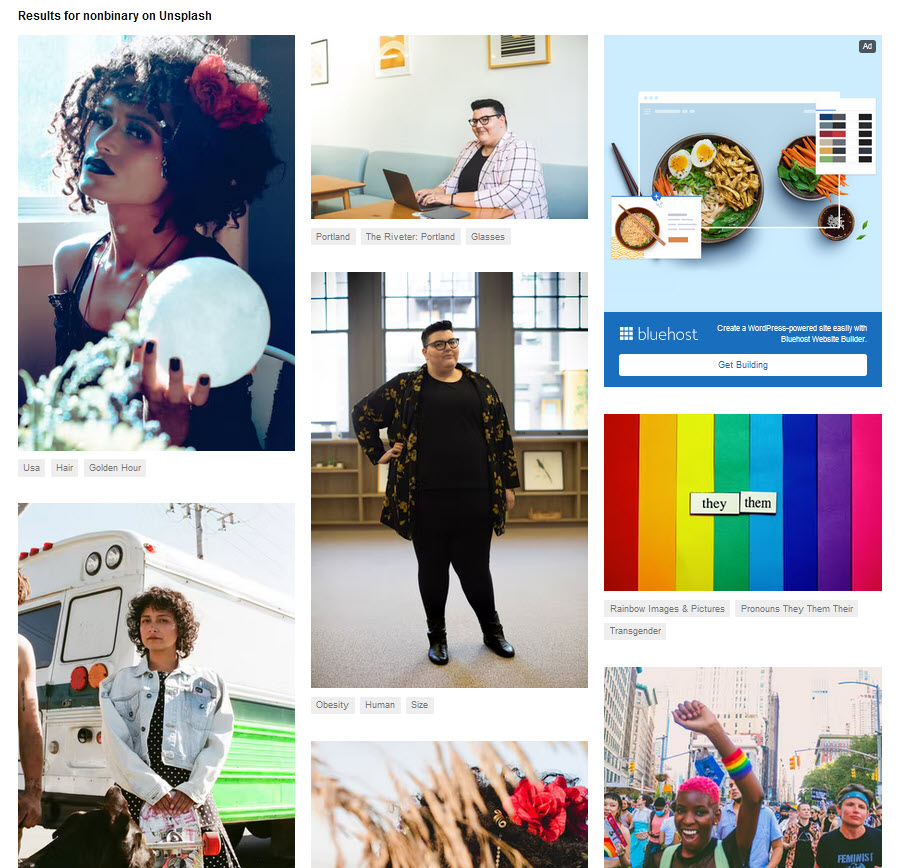

I do straightforward searching with keywords for what I am looking for. As a librarian I get fancy with my search strings and use Boolean connectors. (More info on that below!). For instance, I wanted images of a nonbinary teen. Here’s what I searched . . .

(nonbinary OR non-binary OR “non binary”) AND (teen OR adolescent)

. . . and here’s a screenshot of the results:

Clicking on the image brings it up on the side in a larger format. Then I right click to save it.

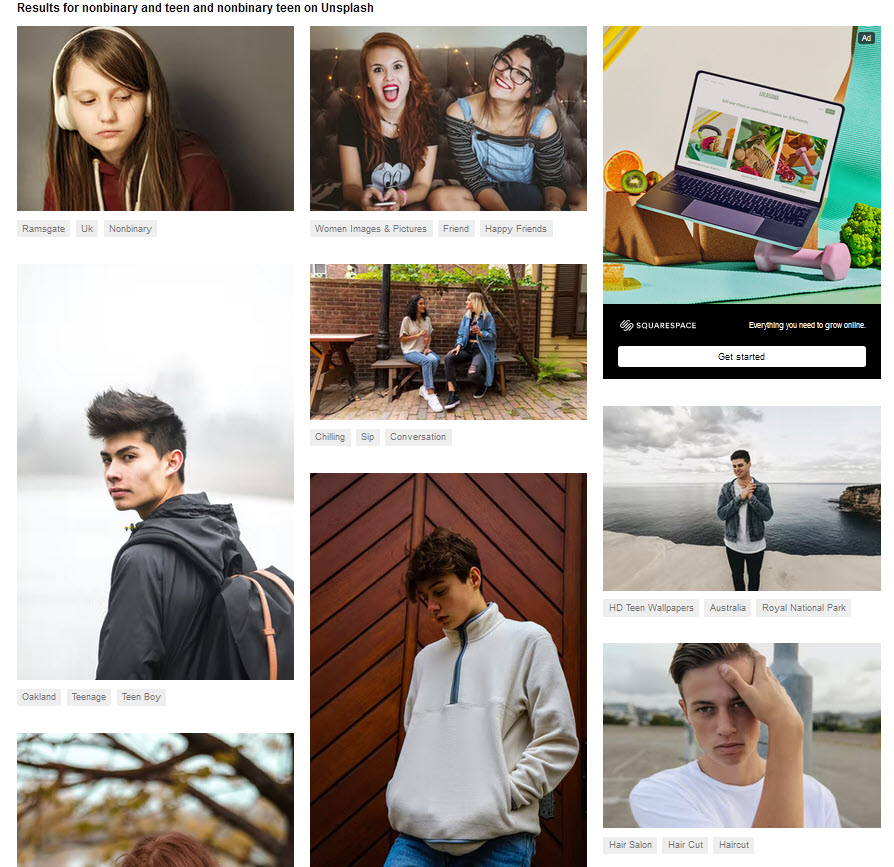

I tried the same search string as I used in Google Images but got some messy results. Not all the images matched what I had in mind. In Boolean searching “AND” means BOTH terms need to be in the results. But with Unsplash images the “AND” feature doesn’t seem to work as well. So I keep my searching terms more general. For instance, just searching nonbinary AND teen or nonbinary teen resulted in the one set of images. Searching just on nonbinary resulted in a very different set, some of which were more personal in nature.

Unsplash results for

nonbinary AND teen and nonbinary teen

Unsplash results for nonbinary

Tumblr is a microblogging social media site. To use it you need to be logged in. I have an account but

do not use it to blog. I use it solely as a writer- and artist-resources tool, for character and idea inspiration, for backstory and setting images, etc. So I mostly follow the blogs of museums, photo historians, so-called artist fan blogs, cities and archaeologists (for the architecture), and fashion historians. Here are just a few I’ve found super useful:

NOTE: Tumblr has a search function that you can use to find feeds on specific topics. Look for the magnifying glass icon and/or the words “Search Tumblr.”

What Words to Use

So, you’ve a character in mind but are trying to find an image to help you zero in while you write. What words should you use in the search box? See those three at the top of this post? For the woman at the left—imagining now that my character is a woman who has perhaps been a little hard used by life so looks a little older than her actual age—I searched these terms in Unsplash: thoughtful woman, older woman, and tired woman. For the teen in the middle I just search for teen and smiling teen. And for the gent at the right I searched older black man and middle aged black man.

I make sure to have an images folder in each of my character folders so it is easier to find them later. When working I have a second monitor to the left of my writing laptop. Then when I am doing major backstory work or character development notes, I put the images of that character or character up on the screen.

Using Images

Something to keep in mind: Many images online are copyrighted. If you plan on making a public or online version of your morgues, you’ll want to make sure you are using images designated as public domain, or that have a Creative Commons license notice, or for which you have permission from the image owner.

Here are some info links about this:

Searching for Images Online (or anything else!)

I mentioned Boolean searching above. Fear not! The name comes from George Boole, a 19th-century English mathematician. He established the rules of symbolic logic. Basically, Boolean searching lets you combine keywords words and phrases to get more focused results. The combining is done by using the words AND, OR, NOT (known as Boolean operators). A search using these operators will limit, broaden, or define your search. Knowing how to put together a search string (as it is called) using the AND, OR, and NOT operators really is a superpower! Click here for the MIT Libraries’ info on how to do Boolean searching.

If you have a question or comment for me, drop me a line via my Contact page.

© J.A. Jablonski 2022. All rights reserved.

HOW TO CITE THIS POST

Jablonski, J.A. (2022, Feb 15 ). Character Morgues: Finding Faces. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website).

https://jajablonski.com/2022/02/15/character-morgues/

IMAGE CREDITS

- Older black man | Photo by Antreina Stone on Unsplash

- Laughing young man | Photo by nrd on Unsplash

- Blue-eyed woman with short blond hair | Photo by Cesar La Rosa on Unsplash

- Gold-covered person | Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

- Geisha | Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

- Distressed woman | Photo by Sam Moqadam on Unsplash

When I was a kid someone told me that waves always come in sevens with the last, seventh wave being the largest. I can remember sitting on the sandy edge of a small lake when summer-swimming with family, sitting and counting the waves as they came in. Maybe the theory doesn’t work in small lakes. I can only recall watching and watching as the rippled lines all looked the same as they hit the shore.

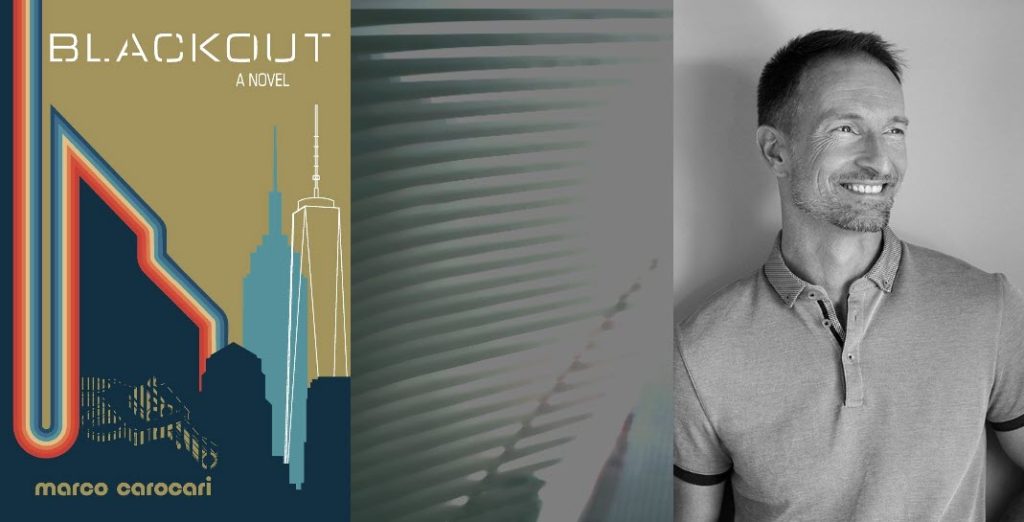

When I was a kid someone told me that waves always come in sevens with the last, seventh wave being the largest. I can remember sitting on the sandy edge of a small lake when summer-swimming with family, sitting and counting the waves as they came in. Maybe the theory doesn’t work in small lakes. I can only recall watching and watching as the rippled lines all looked the same as they hit the shore. Invariably I read books on multiple levels, some of which have little to do with what the book is literally about in terms of plot or genre. That happened reading Carocari where I jumped both.

Invariably I read books on multiple levels, some of which have little to do with what the book is literally about in terms of plot or genre. That happened reading Carocari where I jumped both.

When I began drafting this post back in October, I was inspired by the Halloween season to title it “Stealing Bodies.” For isn’t that what I am doing in a way with my notion of movement and character development?

When I began drafting this post back in October, I was inspired by the Halloween season to title it “Stealing Bodies.” For isn’t that what I am doing in a way with my notion of movement and character development?

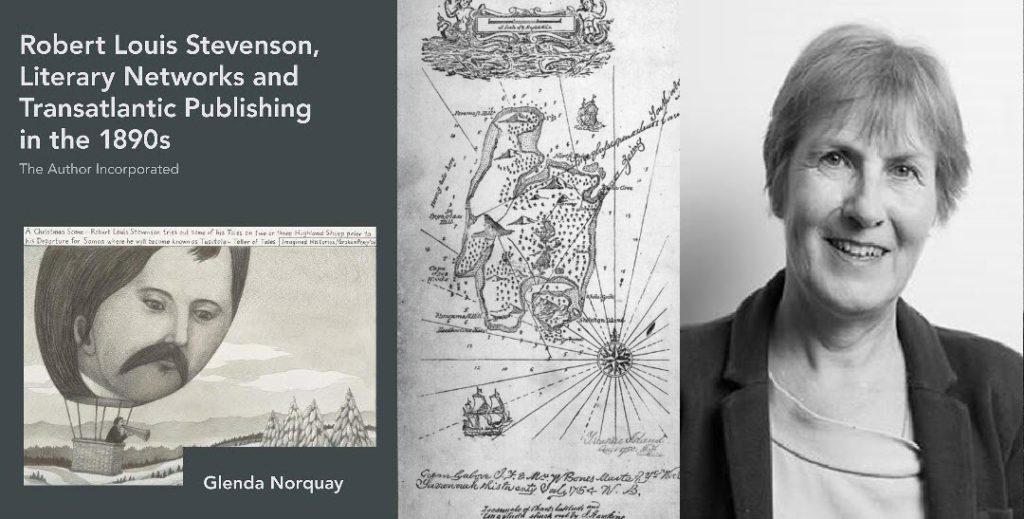

Reading Literary Networks (as I shall refer to Norquay’s book) was a bit like reading two books at once. Scholarly writing can be pedantic and weighty but I didn’t see that here. Norquay’s Introduction is necessarily dense but she outlines her theoretical approach straightforwardly in graceful prose. It is here she lays the groundwork of the book re: geography and the history of publishing in Stevenson’s time.

Reading Literary Networks (as I shall refer to Norquay’s book) was a bit like reading two books at once. Scholarly writing can be pedantic and weighty but I didn’t see that here. Norquay’s Introduction is necessarily dense but she outlines her theoretical approach straightforwardly in graceful prose. It is here she lays the groundwork of the book re: geography and the history of publishing in Stevenson’s time. My tendency as a reader is invariably trinary, with my focus on the pragmatic, the associative, and that which I call the originative flux. As a pragmatic reader I take the story or text as is looking at or for the narrative who, what, when, why, and how. Problematic, sloppy, or casual writing annoys and distracts. If fiction, I wish to be taken, persuaded, challenged, entertained; if nonfiction I want to be informed, accurately and insightfully. And I want the writing done with grace, style, and some measure of verbal power.

My tendency as a reader is invariably trinary, with my focus on the pragmatic, the associative, and that which I call the originative flux. As a pragmatic reader I take the story or text as is looking at or for the narrative who, what, when, why, and how. Problematic, sloppy, or casual writing annoys and distracts. If fiction, I wish to be taken, persuaded, challenged, entertained; if nonfiction I want to be informed, accurately and insightfully. And I want the writing done with grace, style, and some measure of verbal power. Author Info.

Author Info.