Deanna Raybourn | Killers of a Certain Age

“Killers of a Certain Age is sharp and breezy, dark humored and sometimes desperately funny.

It gives women their voice, their rage, and their utter competence.“

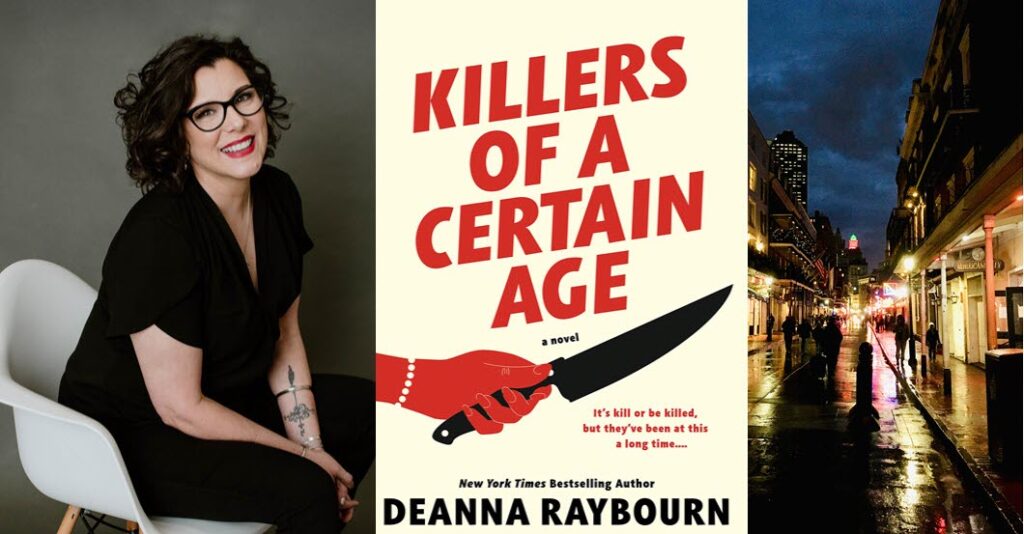

Oh my, I do hope Deanna Raybourn had as much fun writing Killers of a Certain Age (2022) as I did reading it. Focused and witty, Raybourn is utterly in command from the sly, initial author’s note to the final moments and summary remark. Killers is an out-of-the-park home run of a read. [1]

THE STORY

As always, I am interested in the how and how well of a tale, not a specific running through of events. But an overview of the story is needed. This from Raybourn’s website:

“Older women often feel invisible, but sometimes that’s their secret weapon.

Billie, Mary Alice, Helen, and Natalie have worked for the Museum, an elite network of assassins, for forty years. Now their talents are considered old-school and no one appreciates what they have to offer in an age that relies more on technology than people skills.

When the foursome is sent on an all-expenses paid vacation to mark their retirement, they are targeted by one of their own. Only the Board, the top-level members of the Museum, can order the termination of field agents, and the women realize they’ve been marked for death.

Now to get out alive they have to turn against their own organization, relying on experience and each other to get the job done, knowing that working together is the secret to their survival. They’re about to teach the Board what it really means to be a woman—and a killer—of a certain age.”

“It’s kill or be killed, but they’ve been at this a long time….” (from the cover)

I find thrillers stressful reading and usually avoid them. What drew me to Raybourn’s Killers was representation, pure and simple. (And that cover blurb that promised a witty telling!) I am of that same certain age and rarely do I find crime fiction about older women that isn’t of the cozy variety. Now I enjoy me a go-round with Ms. Marple as well as the next, but give her a fierce eye, strong friends of her own kind, and a reason for a little sex and serious revenge, well now, take my money!

Killers of a Certain Age is sharp and breezy, dark humored and sometimes desperately funny. It gives women their voice, their rage, and their utter competence.

CHARACTER, PLOT, & VOICE

I look for characters with heft. The main four women in Killers have solidity; initially a bit too 007 but their eventually revealed backstories flesh them out credibly. Secondary and even minor characters are sketched with sufficient verity. Raybourn tells you how people look with an easy swiftness. There seems to be a future tense cinematic awareness on her part but one can envision one’s own Billie, or Akiko, or Kevin by the way they move, their mannerisms, and the impact of their respective pasts.

The very real notion of what age does to a body, the female body in particular, is not shied away from. I can imagine that there are some who will find these “impossible old bitches” as Billie calls themselves at varous points implausible in terms of their ability to recover quickly enough from various injuries or overextension to save the day, themselves, or each other. That’s the grace of fiction and, in this case, Raybourn’s stylish speed and narrative flash. (Perhaps one can be inspired to higher levels of self care even if covert assassin is not our job title.)

The plot is patterned like a detailed tapestry, every move stitched, every knot tied just so. There is more than one moment that seems incredible, but the flow of the action sweeps you along with a complicit wink. Killers begs to be on the big screen (though I confess I dread that, fearing a glam casting and a male-gazing direction that would ruin all).

And the narrative voice burns with its focus. It is fierce though not always loud—in places it is almost gentle—but the telling is so en pointe, so confident, so almost joyous in its intent that as a reader you feel utterly held and challenged to keep up with the rush of considerable action.

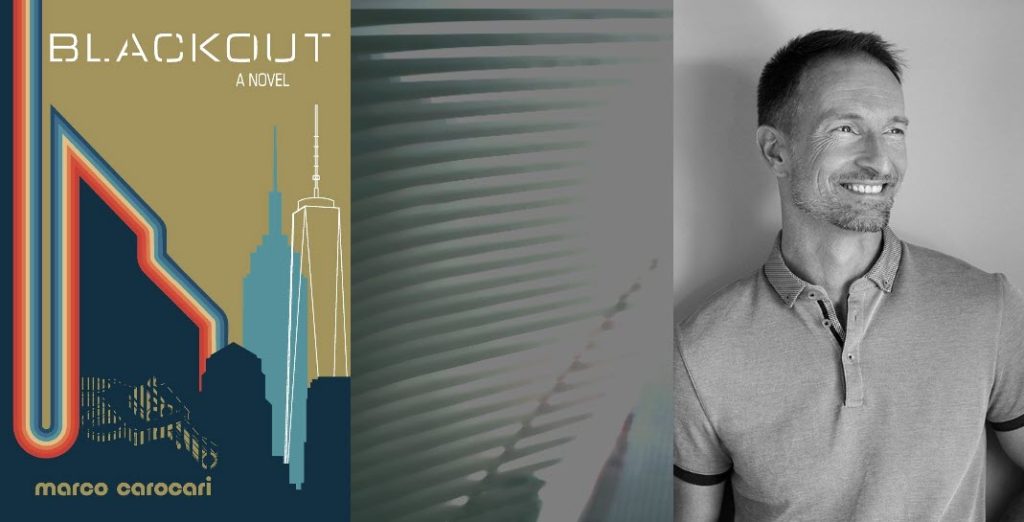

A couple novels of crime & mystery, though utterly different in tone and style, have struck me with a comparable trifecta of well-balanced character, plot, and voice: Dorothy L. Sayers’ Gaudy Night (1935) and Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael’s Penance (1994). [2, 3] And a few have come near: Laurie King’s Touchstone (2008), Marco Carocari’s Blackout (2021), and Jill Paton Walsh’s A Presumption of Death (2002). [4, 5, 6] And, if I may dare to speak of a book I’ve only just begun, Fiona Erskine’s Phosphate Rocks (2021), looks to be shooting for a spot on my list of best crime books. [7]

Writing Hard, Writing Soft

What drives Killers is its vivid, urgent storytelling. I was with these women the entire way, gripped by the nape as it were, to see what they did, what they decided, and to be frank, how they killed and thought about killing, individually and collectively. This last, the very last—how the women thought about their “job”—while only intermittently mentioned was a bit tricky. Killers is meant to be an entertaining read not a discussion of ethics. In the end I think we want to believe we’d be as honorable.

The Sphinxes they’ve been named. Billie, the first person narrator of the present time chapters, is intellectual and ruthless, a natural leader. The remaining trio, Mary Alice, Helen, and Natalie, are less defined but they have their moments in terms of personality and the lethal precision of their respective skill sets. There are men, well-delineated and credible, one perhaps a tad idealized, but for the most part Raybourn keeps the focus on the women.

The Sphinxes are superb, meticulous planners but when things go awry—and we know they will—they are immediately inventive and cool under fire. And they trust and respect each other, not simply for their skills but for who they are and how they think and feel.

But there are grace notes to the story as well, moments of tenderness: when Cassandra Halliday, the women’s Museum mentor in their youth, confronts Billie and uses a painting to make her point; when one of the women recalls an old lover with sensual, tender intensity; when the notion of female solidarity is captured by the making sure hotel maids don’t have to clean up after their ‘work’ and the giving of a ginger drop by one of the old timers to a younger.

Writer as Exemplar

With any of the titles cited above I could imagine something different at certain points, usually having to do with a plot point or a certain aspect of a character. My tweaking in Killers would be only a matter of authorial style but it was a useful exercise to imagine how I might have approached a certain scene differently, useful to imagine why Raybourn made the choices she did.

I learned quite a bit from her re: terse visual description via point of view, practical sentence-to-sentence sequencing, and that notion of utterly trusting one’s reader to be a companion in the process. And while my own idiosyncrasy is to read simultaneously as reader and as writer, never did I feel Raybourn’s heavy hand as author. I like to think I heard her laughter though.

There is real work behind Killers’ blithe ferocity and it is truly impressive. They say the best actors are those who make it look easy, who don’t seem to be acting at all. If Killers of a Certain Age does make it to the cinema, Raybourn has given the cast gold to work with.

Author Bio

“New York Times and USA Today bestselling novelist Deanna Raybourn is a 6th-generation Texan with a degree in English and history from UTSA. Her novels have been nominated for numerous awards including the Edgar, RT Reviewers’ Choice, the Agatha, two Dilys Winns, and the Last Laugh. She launched a Victorian mystery series featuring intrepid butterfly-hunter Veronica Speedwell in 2015. This Edgar-nominated series is ongoing. Her first contemporary thriller, Killers of a Certain Age, chronicles the adventures of four female assassins who must band together against the organization that would rather see them dead than let them retire.” (From the author’s Press Kit)

Raybourn on Mastodon, Instagram, and Twitter

If you have a question or comment for me, drop me a line via my Contact page.

© J.A. Jablonski 2022. All rights reserved.

ABOUT BOOK THOUGHTS

Book Thoughts is an intermittent column within my blog. The essays are both book reviews and book responses. I like to converse with and around the books I read.

How to cite this post

Jablonski, J.A. (2022, Dec 26). Deanna Raybourn|Killers of a Certain Age. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website).

https://jajablonski.com/2022/12/26/deanna-raybourn-killers

IMAGE CREDITS

Header image

-

- Left: Author Portrait of Deanna Raybourn (From her Press Kit)

- Center: Cover of Killers of a Certain Age (From Raybourn’s Press Kit)

- Right: Bourbon Street, New Orleans. Photo by David Reynolds on Unsplash

SOURCES

Disclaimer: As a Bookshop Affiliate (US only) I will earn a commission if you click through on a book title I’ve linked to and make a purchase.

[1] Raybourn, Deanna. (2022). Killers of a Certain Age. Berkley Books. For a complete listing of Raybourn’s’ books see her website.

[2] Sayers, Dorothy L. (1935). Gaudy Night. This link is to the 2012 Harper Paperbacks edition.

[3] Peters, Ellis. (1996). Brother Cadfael’s Penance. Mysterious Press.

[4] King, Laurie R. (2008). Touchstone. Bantam.

[5] Carocari, Marco. (2021). Blackout. Level Best Books.

[6] Walsh, Jill Paton. (2002). A Presumption of Death. St. Martins.

[7] Erskine, Fiona. (2021). Phosphate Rocks. Sandstone Press.

In exploring the craft, the story, and the impact of Chambers’ Monk and Robot books, I don’t want to overlook their pure whimsy and joyfulness. Panga is a lovely little place. The trees, the riverways, the little bugs and great animals; the sheer exuberance of living things is a delight to experience, story and characters aside.

In exploring the craft, the story, and the impact of Chambers’ Monk and Robot books, I don’t want to overlook their pure whimsy and joyfulness. Panga is a lovely little place. The trees, the riverways, the little bugs and great animals; the sheer exuberance of living things is a delight to experience, story and characters aside.

When I was a kid someone told me that waves always come in sevens with the last, seventh wave being the largest. I can remember sitting on the sandy edge of a small lake when summer-swimming with family, sitting and counting the waves as they came in. Maybe the theory doesn’t work in small lakes. I can only recall watching and watching as the rippled lines all looked the same as they hit the shore.

When I was a kid someone told me that waves always come in sevens with the last, seventh wave being the largest. I can remember sitting on the sandy edge of a small lake when summer-swimming with family, sitting and counting the waves as they came in. Maybe the theory doesn’t work in small lakes. I can only recall watching and watching as the rippled lines all looked the same as they hit the shore. Invariably I read books on multiple levels, some of which have little to do with what the book is literally about in terms of plot or genre. That happened reading Carocari where I jumped both.

Invariably I read books on multiple levels, some of which have little to do with what the book is literally about in terms of plot or genre. That happened reading Carocari where I jumped both.

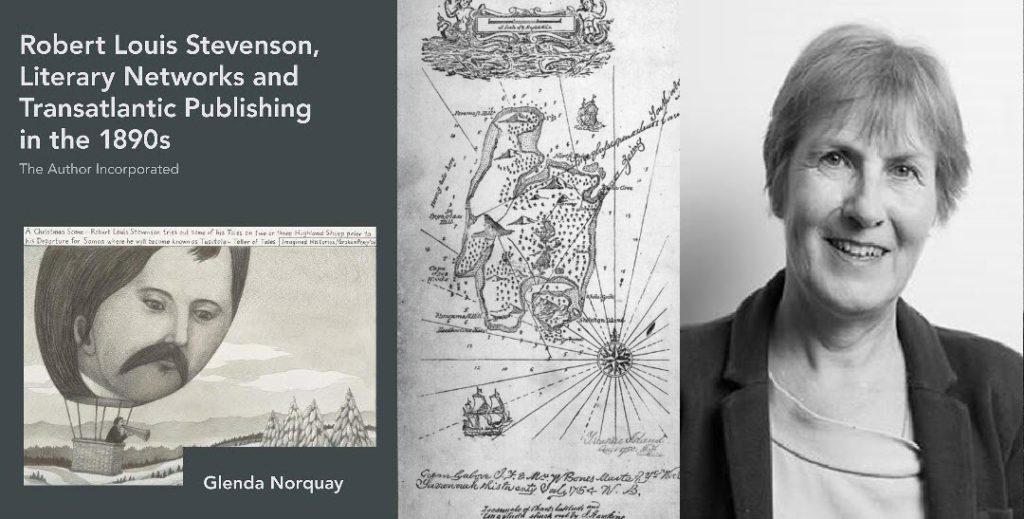

Reading Literary Networks (as I shall refer to Norquay’s book) was a bit like reading two books at once. Scholarly writing can be pedantic and weighty but I didn’t see that here. Norquay’s Introduction is necessarily dense but she outlines her theoretical approach straightforwardly in graceful prose. It is here she lays the groundwork of the book re: geography and the history of publishing in Stevenson’s time.

Reading Literary Networks (as I shall refer to Norquay’s book) was a bit like reading two books at once. Scholarly writing can be pedantic and weighty but I didn’t see that here. Norquay’s Introduction is necessarily dense but she outlines her theoretical approach straightforwardly in graceful prose. It is here she lays the groundwork of the book re: geography and the history of publishing in Stevenson’s time. My tendency as a reader is invariably trinary, with my focus on the pragmatic, the associative, and that which I call the originative flux. As a pragmatic reader I take the story or text as is looking at or for the narrative who, what, when, why, and how. Problematic, sloppy, or casual writing annoys and distracts. If fiction, I wish to be taken, persuaded, challenged, entertained; if nonfiction I want to be informed, accurately and insightfully. And I want the writing done with grace, style, and some measure of verbal power.

My tendency as a reader is invariably trinary, with my focus on the pragmatic, the associative, and that which I call the originative flux. As a pragmatic reader I take the story or text as is looking at or for the narrative who, what, when, why, and how. Problematic, sloppy, or casual writing annoys and distracts. If fiction, I wish to be taken, persuaded, challenged, entertained; if nonfiction I want to be informed, accurately and insightfully. And I want the writing done with grace, style, and some measure of verbal power. Author Info.

Author Info.

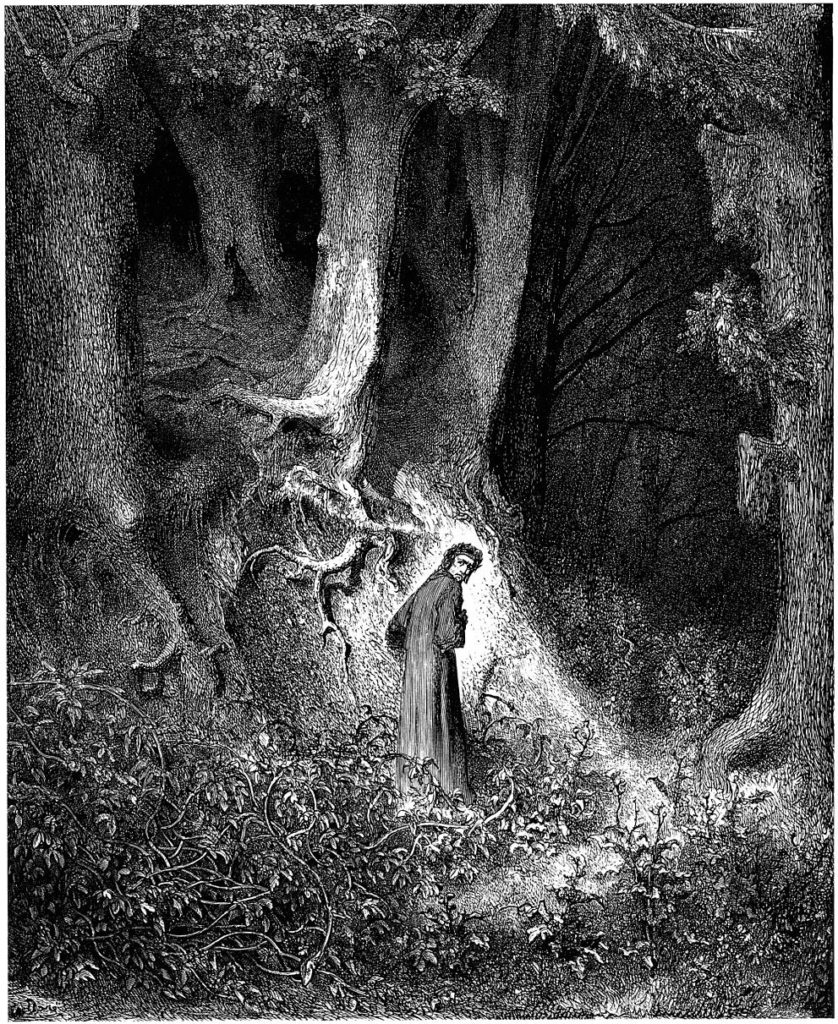

Now, as Dante put it at the beginning of his

Now, as Dante put it at the beginning of his I’ve read many children’s books and, as I began this post noting, many notable works of imaginative fiction. And I am a rather angry reader as a rule. That is, it doesn’t take much for a book to lose my interest or respect. As a former English teacher and theater major, and long-time information professional

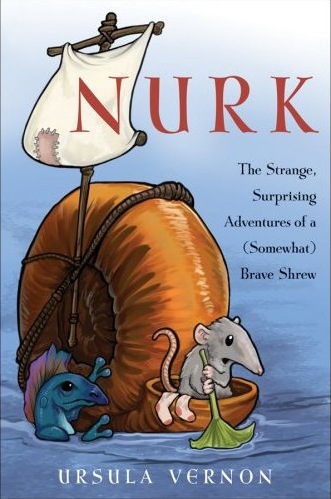

I’ve read many children’s books and, as I began this post noting, many notable works of imaginative fiction. And I am a rather angry reader as a rule. That is, it doesn’t take much for a book to lose my interest or respect. As a former English teacher and theater major, and long-time information professional Immediately upon reading the first page, my hackles twitched. I could hear hobbit and hitchhiker’s guide and all manner of many coy literary allusions. But something Vernon does, and does very well, managed to deflect my inner critic.

Immediately upon reading the first page, my hackles twitched. I could hear hobbit and hitchhiker’s guide and all manner of many coy literary allusions. But something Vernon does, and does very well, managed to deflect my inner critic.