Fictional Letters to Authors & Characters Whose Books I Didn’t, Couldn’t, or Wouldn’t Finish Plus One Kick-In-The-Teeth

“I’ll probably pick up your book again in a few months, Dylan,

after I’ve calmed down, but for now I just cannot get past that one sentence.”

DISCLAIMER

The letters below were inspired by a number of books I’ve read over the past year or so that fell into the DNF* category. Some fell there dramatically, some casually for their lack of originality. One I very much wanted to like, and had it been edited a bit better (about 25 fewer pages wouldn’t have killed the story), I would have gone on to finish. But time is short and my TBR** list far too long. I’ve not included any names (of authors, characters, or book titles). To protect the innocent one might say. But mostly I am just having a bit of summer fun.

* Did Not Finish | ** To Be Read

Dear Doreen,

Dear Doreen,

I want you to know that I tried, I really did, but after five chapters (and rereading all five just to be sure) I just didn’t—couldn’t—care. Okay, I admit that was probably your author’s point. Your friends didn’t care, your boss sure didn’t. If your kids did I don’t know. I didn’t read far enough to find out if you had any. And you didn’t seem to care for yourself much either. So, the promise in the blurb—that you’d discover the true meaning of life at some point, or something like that—wasn’t enough to keep me reading.

Those blurbs also noted, by the way, that your author is known for their writerly empathy. Not quite sure what that means, but they may have slipped up with you. Then again, a famous author with whom I am familiar, blurbed that bit too, the empathy thing I mean. The overall voice of your narrative, though, sounded a tad too much like pity to me.

I am glad you are a fictional character, Doreen. I couldn’t say this if you were real . . . but I just don’t like you. And don’t they say that if a character isn’t likable, even if they are evil, miserable, or whatever, if there isn’t at least something . . . well, I guess you know how this is going to end. I hope you found what you were looking for.

Dear Dylan,

Dear Dylan,

I came across your book by accident, a serendipitous find, when I was searching the public library catalog. I went all Boolean! Aren’t I mad cool? I needed something about a certain cluster of personality disorders AND comorbidity AND (“social behavior” OR “social manifestation”).

It had to be nonfiction and fairly straightforward. Your title was a curious one that suggested your angle on things might contain something unique. But then I read your first words, something along the lines that your father (or maybe it was your stepfather) had the disorder I was interested in.

Puzzled, I closed the your book to read the back-cover blurbs which I hadn’t yet gotten to. (Just so you know, I look at the entire book when I read. It’s a whole package. I learned that in grad school from some gloriously anal-retentive rare books specialist who wore the funkiest, T.S. Eliot-style eyeglasses.) A slew of notables authored all of your blurbs. Serious notables. “Yikes!” I thought. “What did I miss?” Something probably. If I had hung around to find out maybe I wouldn’t be writing this letter.

But while I truly hate the notion that the first sentence of a book makes or breaks it, in this case it was all too sadly true. It was as if your My parent had X wanted to have the same literary impact as Call Me Ishmael. It didn’t. (Then again I didn’t read all of Moby Dick either.) It made me doubt your take on things from the get go. Honestly, I thought I’d picked up a memoir by an insecure second-born with daddy issues. Yeah, I know. Heartless AF. I’ll probably pick up your book again in a few months, Dylan, after I’ve calmed down, but for now I just cannot get past that one sentence. Sorry.

Dear Carlotta,

Dear Carlotta,

I hope you know that an archives, a museum, and a library are not the same thing because it seems your main character hasn’t a clue. I thought your book would be a pleasant escape from looking for comparable titles for my own WIP so my bad there. You could hardly know that I’ve worked in and taught archives and library grad students for a bunch of years.

But that tiny, secret flat in the old wing that the main character rented? (Or did she grow up there as a orphan or with unfeeling parents, which is virtually the same thing isn’t it?) Sorry, but I ran into several I Heart Libraries-themed novels at the same time last year while we were all hunkering down because of (and emotionally escaping from) the Covid horror. (Two had the secret apartment thing going as well.) They all sounded rather the same and rather rote after awhile.

And there was one other thing, Carlotta. I know there are people who do not find libraries (or archives or museums) fascinating places of beauty. Poor them. But people and their interests—no accounting is there, eh? If you turn this mystery into a series though, as seems likely, please do not use up another three quarters of a page in waxing triteness about the glorious smell of old books. We know, we know.

Dear Lucas,

Dear Lucas,

You nailed the setting! Really nailed it! I was there, body and soul. But then the monumental set caved in and buried, smothered, and annihilated the story you were trying to tell. It forced your little coterie of witty, pretty, sexy characters to hold up the sky, as it were, and they just weren’t up to it. But major kudos for having queer characters who were just that, with no grand authorial agenda; just some credible and obvious people who liked whom they liked and everyone was just fine with it. You are my hero, Lucas!

Dear Kevin,

Dear Kevin,

My dear, dear Kevin. You are not the voice of the Deity when it comes to the use and placement of commas, semi-colons, and en- and/or em-dashes. I realize you have writing credentials as old as dirt but surely you know there are reference tools called style guides. There are lots of style guides out there, too, each written for specific audiences, publications, and reasons. And please do note the word guide. That’s guide, not rule. That means recommended usage not carved-in-stone-my-way-or-the-highway. Editors can help you here. Babies won’t die and empires won’t fall if some wee fleck of punctuation is used in a way you’d not deign to use yourself. Take a chill pill.

If you have a question or comment for me, drop me a line via my Contact page.

© J.A. Jablonski 2022. All rights reserved.

How to cite this post

Jablonski, J.A. (2022, June 22). Fictional Letters to Authors & Characters Whose Books I Didn’t, Couldn’t, or Wouldn’t Finish Plus One Kick-In-The-Teeth. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website). https://jajablonski.com/2022/06/22/fictional-letters-to-author/

IMAGE CREDITS

Header image

-

- Collection of of old envelopes. From PublicDomanPictures.net.

- Angry-faced fountain pen & ink blot. From i2Clipart.

- Collection of of old envelopes. From PublicDomanPictures.net.

Postage stamps & cancellation mark. All in Public Domain

In this time of intense social media bombardment, of frantic and dangerous world events, of private personal and familial concerns, letting one’s mind simply go is not an easy thing. I try to turn away from social media at least twice a week. And by away I mean just that. It’s not easy since I am sitting at my desk with my several work monitors; which is why I can only manage it twice a week! I do much of my writing research online. But I force myself to do it—not open any new tabs on my laptop, shut down my phone. Sometimes it takes me several times to get myself to do this.

In this time of intense social media bombardment, of frantic and dangerous world events, of private personal and familial concerns, letting one’s mind simply go is not an easy thing. I try to turn away from social media at least twice a week. And by away I mean just that. It’s not easy since I am sitting at my desk with my several work monitors; which is why I can only manage it twice a week! I do much of my writing research online. But I force myself to do it—not open any new tabs on my laptop, shut down my phone. Sometimes it takes me several times to get myself to do this.

When I was a kid someone told me that waves always come in sevens with the last, seventh wave being the largest. I can remember sitting on the sandy edge of a small lake when summer-swimming with family, sitting and counting the waves as they came in. Maybe the theory doesn’t work in small lakes. I can only recall watching and watching as the rippled lines all looked the same as they hit the shore.

When I was a kid someone told me that waves always come in sevens with the last, seventh wave being the largest. I can remember sitting on the sandy edge of a small lake when summer-swimming with family, sitting and counting the waves as they came in. Maybe the theory doesn’t work in small lakes. I can only recall watching and watching as the rippled lines all looked the same as they hit the shore. Invariably I read books on multiple levels, some of which have little to do with what the book is literally about in terms of plot or genre. That happened reading Carocari where I jumped both.

Invariably I read books on multiple levels, some of which have little to do with what the book is literally about in terms of plot or genre. That happened reading Carocari where I jumped both.

When I began drafting this post back in October, I was inspired by the Halloween season to title it “Stealing Bodies.” For isn’t that what I am doing in a way with my notion of movement and character development?

When I began drafting this post back in October, I was inspired by the Halloween season to title it “Stealing Bodies.” For isn’t that what I am doing in a way with my notion of movement and character development?

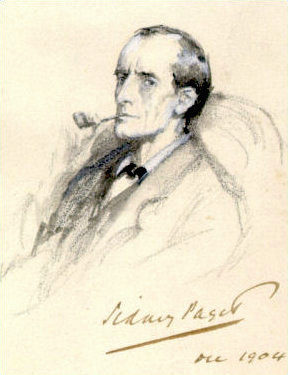

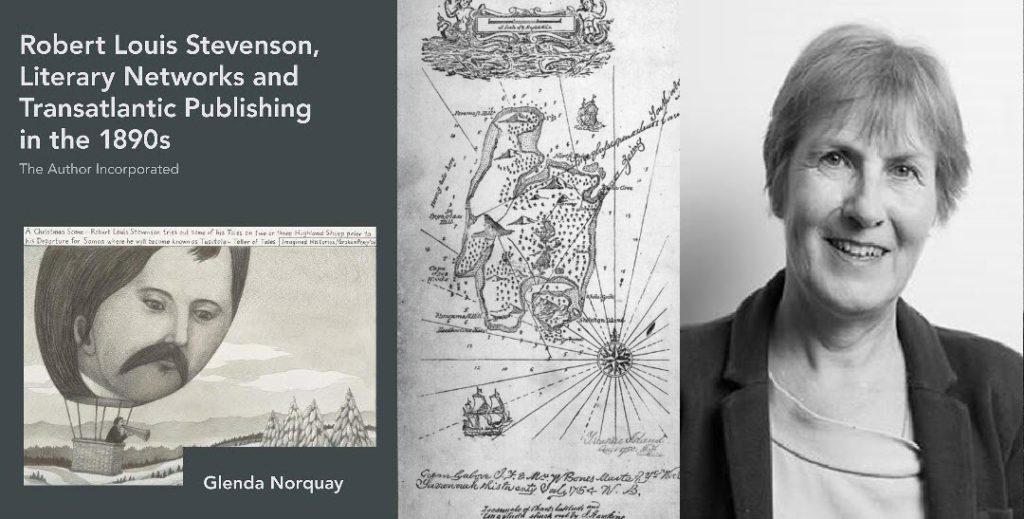

Reading Literary Networks (as I shall refer to Norquay’s book) was a bit like reading two books at once. Scholarly writing can be pedantic and weighty but I didn’t see that here. Norquay’s Introduction is necessarily dense but she outlines her theoretical approach straightforwardly in graceful prose. It is here she lays the groundwork of the book re: geography and the history of publishing in Stevenson’s time.

Reading Literary Networks (as I shall refer to Norquay’s book) was a bit like reading two books at once. Scholarly writing can be pedantic and weighty but I didn’t see that here. Norquay’s Introduction is necessarily dense but she outlines her theoretical approach straightforwardly in graceful prose. It is here she lays the groundwork of the book re: geography and the history of publishing in Stevenson’s time. My tendency as a reader is invariably trinary, with my focus on the pragmatic, the associative, and that which I call the originative flux. As a pragmatic reader I take the story or text as is looking at or for the narrative who, what, when, why, and how. Problematic, sloppy, or casual writing annoys and distracts. If fiction, I wish to be taken, persuaded, challenged, entertained; if nonfiction I want to be informed, accurately and insightfully. And I want the writing done with grace, style, and some measure of verbal power.

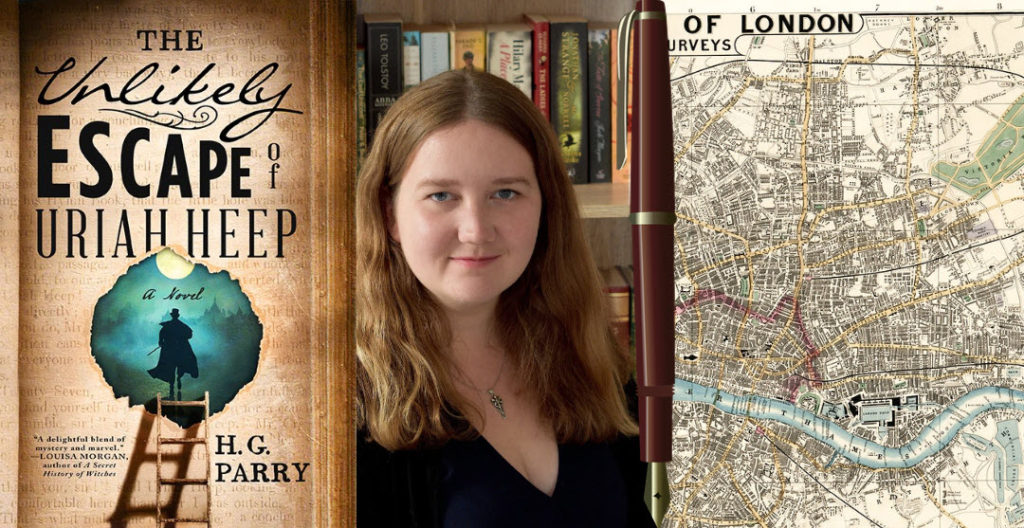

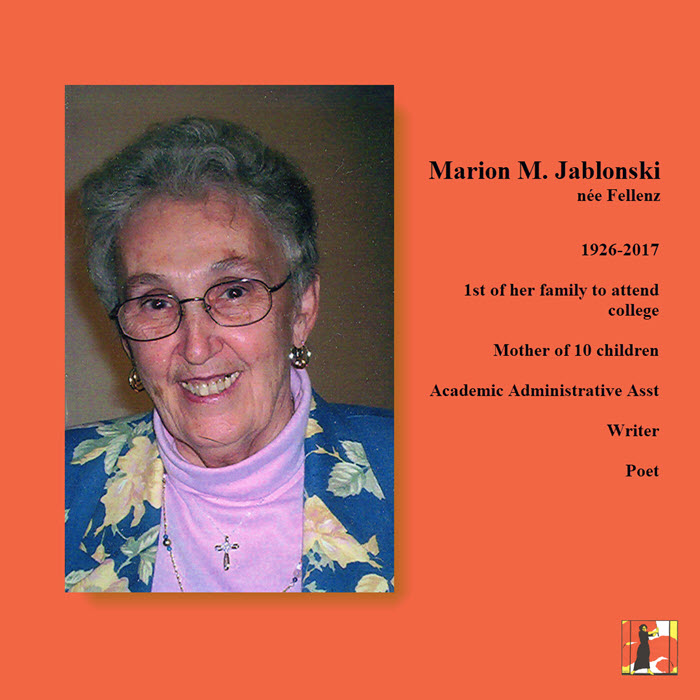

My tendency as a reader is invariably trinary, with my focus on the pragmatic, the associative, and that which I call the originative flux. As a pragmatic reader I take the story or text as is looking at or for the narrative who, what, when, why, and how. Problematic, sloppy, or casual writing annoys and distracts. If fiction, I wish to be taken, persuaded, challenged, entertained; if nonfiction I want to be informed, accurately and insightfully. And I want the writing done with grace, style, and some measure of verbal power. Author Info.

Author Info.