Gray Areas and Content Warnings

“. . . the gray area between “good” and “bad” and include [s]situations we wouldn’t want to experience in real life

— and just like any story, they’re not for everyone.”

~ Jami Gold

I’ve been crafting a content warning statement that addresses one of my series’ ongoing themes: the slow healing of trauma. Whether or not to include a warning was something I had to consider.

Around the early 2000s, the use of content warnings (also called trigger warnings) become prevalent in education. Framed as trauma-informed pedagogy, the notion is that a person who has experienced trauma can be impacted by the content of a given environment. The concept is often seen in writing now with the author needing to decide how extensively they will want to warn their readers, if at all. A key issue is how much a writer “owes” the people who read their books.

I’ve looked at statements written by other authors and one, Jami Gold, an author of paranormal romance, focuses specifically on the reader experience She notes that in addition to “explor[ing] the gray area between ‘good’ and ‘bad’” she will “include situations we wouldn’t want to experience in real life,” sensibly concluding that “and just like any story, they’re not for everyone.” [1]

Jami Gold’s commentary focuses more on the reader experience. She adds that “While some readers appreciate a heads up of content that might be uncomfortable for them, many readers want to experience a story without any hints of what’s to come.” [2]

Elizabeth A. Cartwright (Liz), an editor, graphic designer, and author takes the discussion a bit further in her 2024 thoughtful and useful essay about content warnings. She strikes a balance which I like. In her paragraph with the heading “Do I need to use content warnings?” she threads the careful needle of coddling or censorship. “Others,” she says, “will go as far as to say content warnings encourage censorship and hamper learning, by allowing people to shy away from content that would be otherwise valuable to consume.” [3]

There’s some historical sociology going one here, I warrant, of the variety of people who grew up under a tough love regime or were simply ignored. A kind of ‘boomer mentality’ I suspect, where the idea is “well I had it rough and survived, so you can/should too.” Fast forward to the helicopter parenting era where it seems every emotion and experience is to be protected and shielded.

Having been at the receiving end of sexual assault, stalking, and harassment, I have reflected on what sort of warnings I myself would want. In theory, I am the perfect audience for warnings. For me, and this is strictly personal (I would not presume my experience and decision applies to anyone but myself), I would prefer not to have them on page (on an author’s website, if under its own heading, would be okay). But my situation is perhaps unusual. Besides working with a therapist, which let me get a grip on things, I have two degrees in reading and critiquing literature and two more in analyzing and classifying works in the humanities and social sciences. Therapy and education, and later several decades as an information professional specializing in indexing, qualitative concept analysis, and information finding have given me a kind of objectivity in terms of reading texts.

Objectivity as in terms of distance, not approval. And that’s with regard to text only. I am extremely visual with an imagination that can go wild, so I avoid the horror and thriller genres both on screen and on page. I don’t need to provide fodder for nightmares.

As my current writings are murder mysteries, I have given considerable thought as to how extensively my readers should be forewarned. I don’t think it is my responsibility to protect people as no one is forcing them to read my books. I do appreciate, though, that I am writing outside the so-called cozy or sentimental approach, not thrillers precisely, but stories that have intense, graphic moments. And I respect my readers and the times, which are so difficult now, and so hurtful.

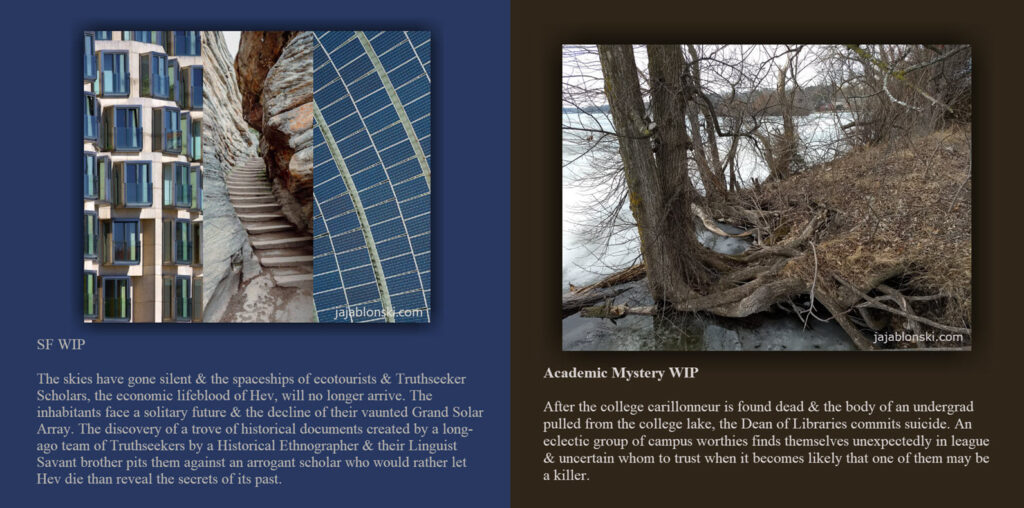

What I am doing, and quite intentionally, is exploring how a small group of people diverse in terms of their personalities, genders, sexualities, expertise, personal histories, and ethnicities find themselves gradually creating a chosen family over time. Their individual stories contain difficulties and traumas that some readers may find difficult.

If you have a question or comment for me, drop me a line via my Contact page. You can see a wider view of my creative world on my Instagram page.

© J.A. Jablonski 2025. All rights reserved.

How to cite this post

Jablonski, J.A. (2025, Sept 16). Gray Areas and Content Warnings. Blog post. J.A. Jablonski (website).

https://jajablonski.com/2025/09/16/content-warnings/

SOURCES

[1, 2] From Gold’s website page on Content Guidance: https://jamigold.com/for-readers/guidance/

[3] Cartwright’s blog post can be found here: https://www.ec-editorial.com/post/content-warnings

IMAGE ID & CREDITS

Header image is a close-up of the female face from “The Green Masque” by Oswald Birley (1922) superimposed over a swirling blue background. There was no AI used in creating this slide. Some years ago I used the old PICAS image editor to “posterize” the face, then recently changed its hues and fading via the SnagIt Editor app.

Photo Credit: The blue background by Pawel Czerwinski via Unsplash.

In a recent Bluesky thread, Ann Leckie, author of the Hugo award-winning Ancillary Justice, commented on the shift in “straightforward narration/exposition” noting that “young readers aren’t used to it.” [2, 3] It’s the impact of social media there to my mind and the generational shift in the content and approach found now in high school and college literary education. Younger educators and their younger readers haven’t learned how to read literature where a story is told via longer narration and description. I saw this already some years back when, as an assistant bookstore manager and VHS was the format for the day, I was regularly asked by students “where the videos for all the books were.” It goes beyond the Which is better, book or movie? trope. The movie is the book for many.

In a recent Bluesky thread, Ann Leckie, author of the Hugo award-winning Ancillary Justice, commented on the shift in “straightforward narration/exposition” noting that “young readers aren’t used to it.” [2, 3] It’s the impact of social media there to my mind and the generational shift in the content and approach found now in high school and college literary education. Younger educators and their younger readers haven’t learned how to read literature where a story is told via longer narration and description. I saw this already some years back when, as an assistant bookstore manager and VHS was the format for the day, I was regularly asked by students “where the videos for all the books were.” It goes beyond the Which is better, book or movie? trope. The movie is the book for many. After reading Leckie’s thread, I picked up Ancillary Justice. I’ll be reading her entire Imperial Radch trilogy this winter as I turn to my SF project, looking to study her approach to world building (as well as reviewing Le Guin, Becky Chambers, H.G. Parry, Ada Palmer, and N.K. Jemisin for the same reason). Leckie’s narration, blended with her precise style of exposition, is more heavily detailed and drawn out than I remember from my first reading some eight years ago. Then, almost immediately absorbed by the story, Leckie’s method was less visible to me. This time, though, it is visible, and I find myself resisting. They’re intriguing, the details, but also a bit much; not too rich, simply much. I find myself skimming where before I slowed and marinated in it all. And I fret for this, that I have become somehow altered by social media as well.

After reading Leckie’s thread, I picked up Ancillary Justice. I’ll be reading her entire Imperial Radch trilogy this winter as I turn to my SF project, looking to study her approach to world building (as well as reviewing Le Guin, Becky Chambers, H.G. Parry, Ada Palmer, and N.K. Jemisin for the same reason). Leckie’s narration, blended with her precise style of exposition, is more heavily detailed and drawn out than I remember from my first reading some eight years ago. Then, almost immediately absorbed by the story, Leckie’s method was less visible to me. This time, though, it is visible, and I find myself resisting. They’re intriguing, the details, but also a bit much; not too rich, simply much. I find myself skimming where before I slowed and marinated in it all. And I fret for this, that I have become somehow altered by social media as well.

I also grew up reading and enjoying Marvel and DC comics—particularly X-Men and Batman—as Saturday morning and after school cartoons showcased these characters. When deciding my career goals, I had an inkling that it was to write stories via comics. Comics, and now graphic novels show a tremendous visual experience. Pictorial compositions explain the words; the words explain the pictures. It was a glorious calligraphy of shape and line.

I also grew up reading and enjoying Marvel and DC comics—particularly X-Men and Batman—as Saturday morning and after school cartoons showcased these characters. When deciding my career goals, I had an inkling that it was to write stories via comics. Comics, and now graphic novels show a tremendous visual experience. Pictorial compositions explain the words; the words explain the pictures. It was a glorious calligraphy of shape and line.

Koshiki had been my boss at a Japanese noodle restaurant in Lowertown Saint Paul called Tanpopo Noodle Shop. She, her husband Ben, her mother, and brother Ira, as well as an incredible, tightly knit team of kitchen and serving staff operated Tanpopo at a standard of excellence that drew me back multiple times to eat delicious soba and udon noodles.

Koshiki had been my boss at a Japanese noodle restaurant in Lowertown Saint Paul called Tanpopo Noodle Shop. She, her husband Ben, her mother, and brother Ira, as well as an incredible, tightly knit team of kitchen and serving staff operated Tanpopo at a standard of excellence that drew me back multiple times to eat delicious soba and udon noodles.

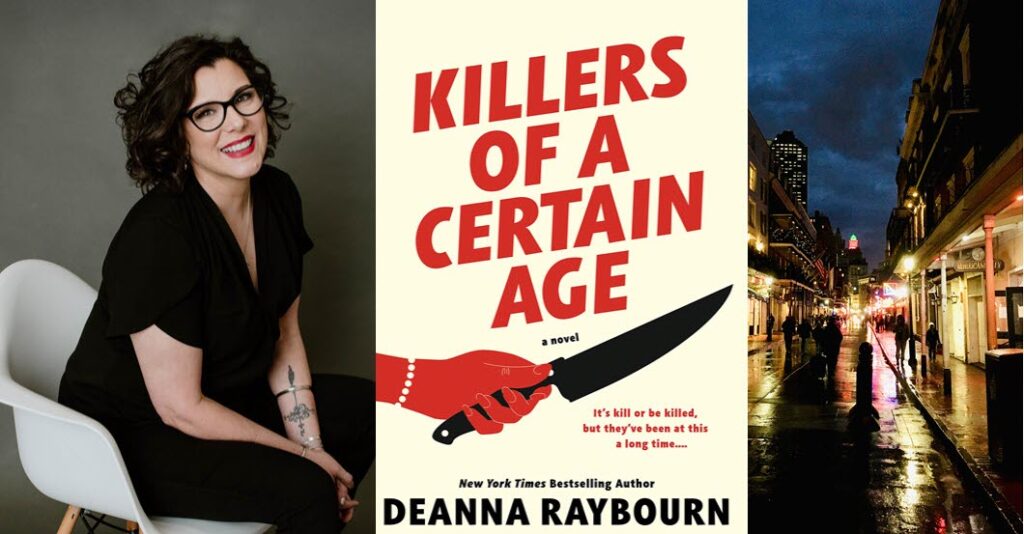

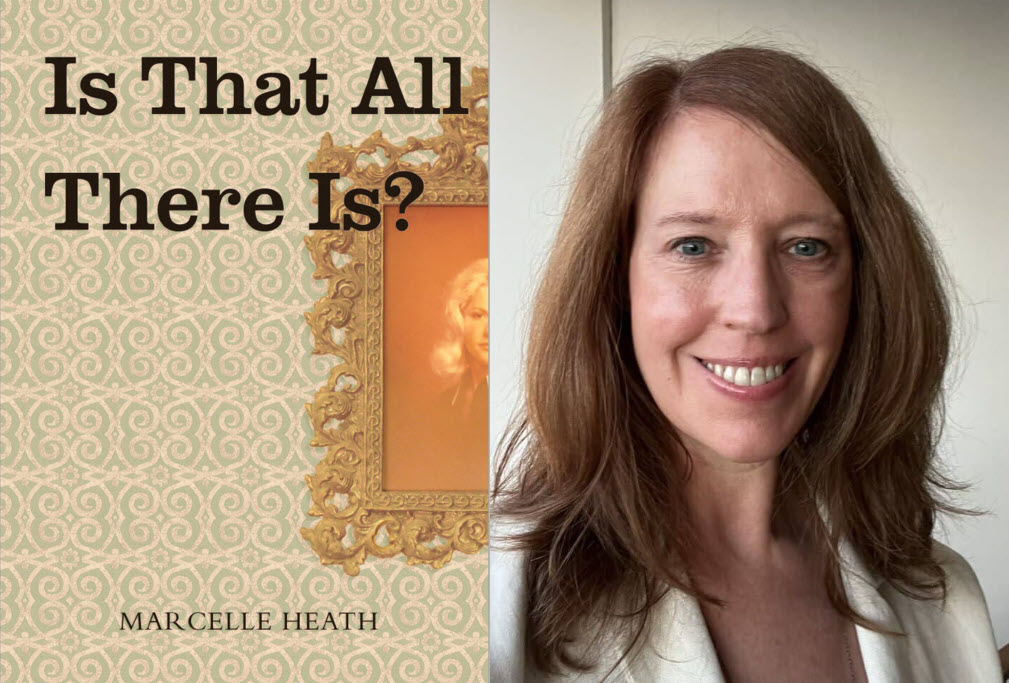

Author Marcelle Heath is the author of the recent Is That All There Is? (2022), a collection of short stories. [1] Her writing is rich, evocative, and well-crafted, her eye for detail, personality, and the dynamics of human interaction finely tuned.

Author Marcelle Heath is the author of the recent Is That All There Is? (2022), a collection of short stories. [1] Her writing is rich, evocative, and well-crafted, her eye for detail, personality, and the dynamics of human interaction finely tuned.

I rarely purchase clothing new. I like garb that has a story, preferably a long and involved story. Most of what I wear is thrifted, hand-me-overs from siblings, sewn by me, or something I made or acquired 20 or 30 years ago. There were no such things as Tall Shops when I grew up, Even now most store-sold clothing designed for women is unappealing: the garments are often poorly made and their design is generic and assumes gender roles for the wearer. Big and tall men’s stores often have better made products but the overt modern “guy-ness” of the designs is boring for me.

I rarely purchase clothing new. I like garb that has a story, preferably a long and involved story. Most of what I wear is thrifted, hand-me-overs from siblings, sewn by me, or something I made or acquired 20 or 30 years ago. There were no such things as Tall Shops when I grew up, Even now most store-sold clothing designed for women is unappealing: the garments are often poorly made and their design is generic and assumes gender roles for the wearer. Big and tall men’s stores often have better made products but the overt modern “guy-ness” of the designs is boring for me.